- Feb 10

- 5 min read

Walk into almost any martial arts school and the structure is familiar. Warm up.

Technique of the day.

Drill it.

Maybe pressure test it.

The assumption is simple and rarely questioned. If you give someone the right technique, they will be safer.

The problem is that most violence does not start where most training does.

Real-world situations do not begin at striking range, in a squared stance, with mutual consent. They begin minutes, hours, or in some cases days earlier. They begin with positioning, attention, boundaries and choices. When we teach techniques as the starting point, we are training people for the middle of the problem, that they may never either never enter or are too late.

This is not an argument against techniques. Techniques matter. But without a frame work, technique becomes disconnected tools waiting for the wrong moment.

Self-defense in particular needs a timeline.

The Missing Frame Work

Most martial arts train a very particular moment in time: Contact.

Everything before contact is treated as awareness, common sense, or intuition at best. Sure, it might be mentioned in passing, but it is usually just implied rather than trained or discussed.

Everything after contact is even worse. It is largely ignored all together, as if the moment that physical techniques end, the encounter simply stops. In reality, those two zones determine whether physical skills are even needed in the first place and whether using them actually solves the problem.

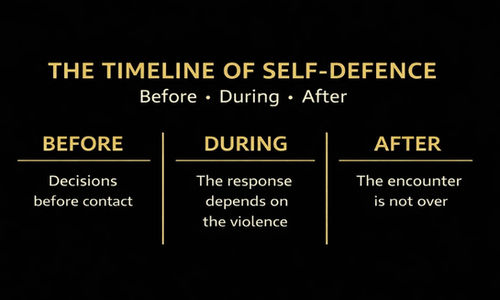

When we teach self-defense, the material is organised around a simple model: Before, During, and After.

Not as phases you must pass through in order, but as a way to understand where you are at in an encounter and what skills will make sense in that moment.

When we ignore this timeline, we end up teaching good people to make bad decisions at the worst possible time.

Before is Where Most Encounters Are Won

The “Before” phase includes awareness, environment, positioning, behavior and history (a factor we often forget in training). It is where people either get selected, de-selected, or never noticed at all.

This is not about paranoia. It is about understanding how humans choose targets.

Predatory violence tends to flow toward ease, isolation, distraction, and compliance. Social violence tends to escalate through ego, misunderstanding, and emotional momentum. Both of these processes happen long before fists fly.

If someone can read distance, recognize when a conversation feels wrong, manage space, set boundaries, and leave early, they may never need the techniques that they spent years perfecting.

Teaching technique first often trains people to wait too long. They stay in interactions they should exit. They stand when they should move. They focus in what to do if it turns physical instead of preventing it from getting there.

A strong self-defense curriculum trains avoidance as a skill, not a personality trait.

The Interview Happens Before the “Fight”

One of the most overlooked parts of violence is what most experts call “the interview”.

This is the testing phase. It might look friendly or awkward or slightly aggressive. Someone asks a question, steps closer, invades space, or applies social pressure. They are getting data on you. Will you comply, freeze, escalate, or just disengage.

Martial artists accidently train for this all the time, just not in a helpful way.

We teach students to be polite, cooperative, and focused on the drills. We discourage them from breaking contact, walking away, or using their voice assertively unless a rule set allows it. Over time this creates training scars.

Students become very good at staying in bad positions waiting for permission to act.

Teaching the interview, means teaching people to recognize testing behavior, respond early, and create exits without turning the situation into a challenge match. This is where posture, boundaries, tone, hand position, and angles matter more than combinations or take downs.

During is Not One Thing

If contact does happen, the “During” phase is not a singular category. Different types of violence demand different responses.

Mutual combat, social violence, and predatory assault are not interchangeable problems. Treating them as such is how people apply the wrong solution at the worst possible moment.

A strategy that works beautifully in a consensual fight can escalate social conflict. A strategy that relies on fairness and rules can be disastrous against a predator. A strategy that assumes you must dominate can trap you in a spot you should be exiting.

This is why the first skill you need in the “During” phase is not a strike or throw. It is recognition.

Once you understand what type of violence you are dealing with, techniques become relevant again. Clinch, control, striking, takedowns, and ground skills all have their place. But they are supporting tools, not the opening move.

Exit is Not an Option

One of the biggest blind spots in martial arts training is accessing exits.

Students learn how to engage, how to counter and how to continue. They rarely learn disengage cleanly, create space, and leave safely.

Winning and exchange does not mean you have won the encounter.

An effective self-defense response includes breaking contact, managing pursuits, using obstacles, and choosing when not to continue. Exit should be trained as deliberately as entry.

If your training ends with domination but no strategy on how to leave safely, you are only solving a part of the problem.

After Matters

What happens immediately after an encounter can have consequences that last far longer than the event itself.

Injury assessment, emotional regulation, interacting with witnesses, and reporting all matter. They influence medical and legal outcomes, and personal recovery.

Ignoring the “After” phase leaves students unprepared for the reality that violence does not end when the last strike lands, and shows them the consequences of going hands on.

A complete self-defense education respects the whole timeline, not just the dramatic moments in the middle.

Technique Belongs Inside Context

This is the key point that instructors often miss.

Techniques are not wrong. Teaching them without the context of goals is.

When students understand where they are in the timeline, techniques make more sense. They choose better options, apply them earlier or later as needed, and they disengage sooner. They stop forcing solutions and start solving problems.

The timeline does not replace martial arts. It organizes them.

For instructors this is an upgrade, not a rejection. You can keep teaching the art you love while giving students a model that makes it more effective in the modern world.

Self-defense does not start with contact. It starts with choices.

And the earlier we teach those options, the safer our students become.

This framework is explored in greater depth in The Timeline of Self Defense: Before, During, and After Violence, releasing May 5th, from YMAA publishing.