Throws & Strikes: Use Them the Way They Were Designed!

- Marcus Day

- May 23, 2024

- 8 min read

For traditional martial artists, the line between styles can seem concrete: Hard styles strike, and soft styles grapple. But anyone who’s studied the history and applications of traditional styles knows better. Most hard styles like karate have many grappling techniques in their curricula. And styles like judo and aikido (if taught correctly) have basic strikes and even kicks.

Trouble can arise when the applications of such techniques are confused. Sticking with the example of karate and judo, both arts have similar basic techniques when it comes to striking and grappling, but the applications of said techniques are far from the same. And they shouldn’t be. Hard styles use grappling to set up strikes, and soft styles use strikes to set up grappling.

Traditional martial arts in the modern era rarely emphasize these elements even though they’re embedded deeply within every style. For judo and karate, sport competition has eroded much of the practice of the hard-soft aspects of the arts. And aikido in most of its modern incarnations has lost its effective striking fundamentals. In the introduction to his instructional-cum-critique Atemi: The Thunder and Lightning of Aikido, Walther G. Von Krenner laments the current state of the art: “His [O-Sensei’s] ideals of peace and harmony seem to have supplanted modern practitioners’ desire for effective techniques and fighting skills. They view the founder’s spiritual goals as more important than the art’s physical techniques.”

Even though aikido has been an easy target for criticism, karate isn’t above reproach, either. There are grappling techniques (and defenses against grappling techniques) in the kata of every karate style, but walk into any dojo in America and there’s a good chance not even the sensei will know the bunkai (applications) of the forms, let alone how to apply them in a real fight. Blame it on sport martial arts, lazy instruction or the prevalence of McDojos — whatever the cause, bunkai is becoming a lost art in its own right.

Two Skill Sets

As with so many things in the martial arts world, everyone has his or her own ideas of what works, what doesn’t and what should be left on the cutting-room floor of a bad kung fu movie. But they aren’t always correct. These days, we take for granted the need to be a well-rounded fighter, but when I started martial arts, I remember many so-called masters dismissing the need for grappling altogether. “Just don’t go to the ground,” they would say when someone broached the subject. Decades of that sort of thinking are why so many traditional styles find themselves playing catch-up with the realities of self-defense and fighting.

Another problem crops up when a traditional stylist who’s spent 20 years training on one end of the hard-soft spectrum thinks he can close the gap after a year or two of cross-training. You can’t. Even someone who’s done both hard and soft styles since the beginning very often leans one way or the other as a matter of preference or aptitude. This distinction isn’t meant to harden the lines between traditional styles, only to ensure you’re playing to your style’s strengths. In his seminal work Karate-Do Kyohan, Gichin Funakoshi sums up his view on karate’s throwing techniques: “Softness is necessary to become hard, and hardness is necessary to become soft. To begin with, both softness and hardness are one.”

He expands on this premise in Karate Jutsu: The Original Teachings of Gichin Funakoshi: “‘Hard’ exists only because ‘soft’ exists, and so a combination of the two is certainly advantageous.”

Done Differently

In application, there are differences. A throw in karate isn’t the same as a throw in judo or aikido. The same is true of strikes in soft styles. Hard and soft styles have different methodologies, so it stands to reason that their application of similar techniques would be different, as well. In Karate Jutsu, Funakoshi says, “In contrast to jujutsu, karate might be considered a ‘hard’ art, and throwing and taking down an opponent are not fundamental aims.”

It’s important to note this distinction. Someone trained primarily in karate, taekwondo, boxing or any art that relies mostly on striking will never be as good at effecting a throw or a grappling move as someone trained primarily in judo, aikido or Brazilian jiu-jitsu. The same is true of a soft stylist using strikes. There are certainly grapplers who have the physical strength to throw a punch that would knock out anyone unfortunate enough to be on the receiving end of it — take a look at any high-level wrestler or judoka — but strength and skill are two different things. And a strong grappler would lose in the boxing ring just as quickly as a strong boxer would lose on the wrestling mat. As Funakoshi said, you must know the fundamental aim of your style in order to add techniques that will suit it.

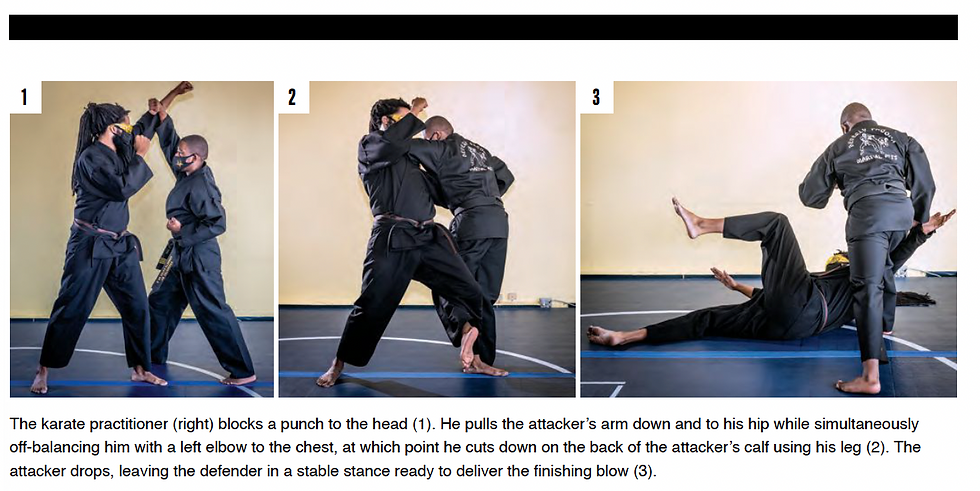

Both karate and judo have versions of osoto gari, or major outer reap. In the classical judo version of this throw, you off-balance your opponent to the rear before swinging your leg high, hooking your opponent’s calf and reaping his leg into the air. The follow-through is important here. Your body is like a pendulum: As your leg reaps into the air, lifting your opponent’s leg, your head goes down, driving his body hard into the ground. The throw alone is meant to injure the attacker. If it doesn’t, the judoka can follow up with an immobilization or joint lock.

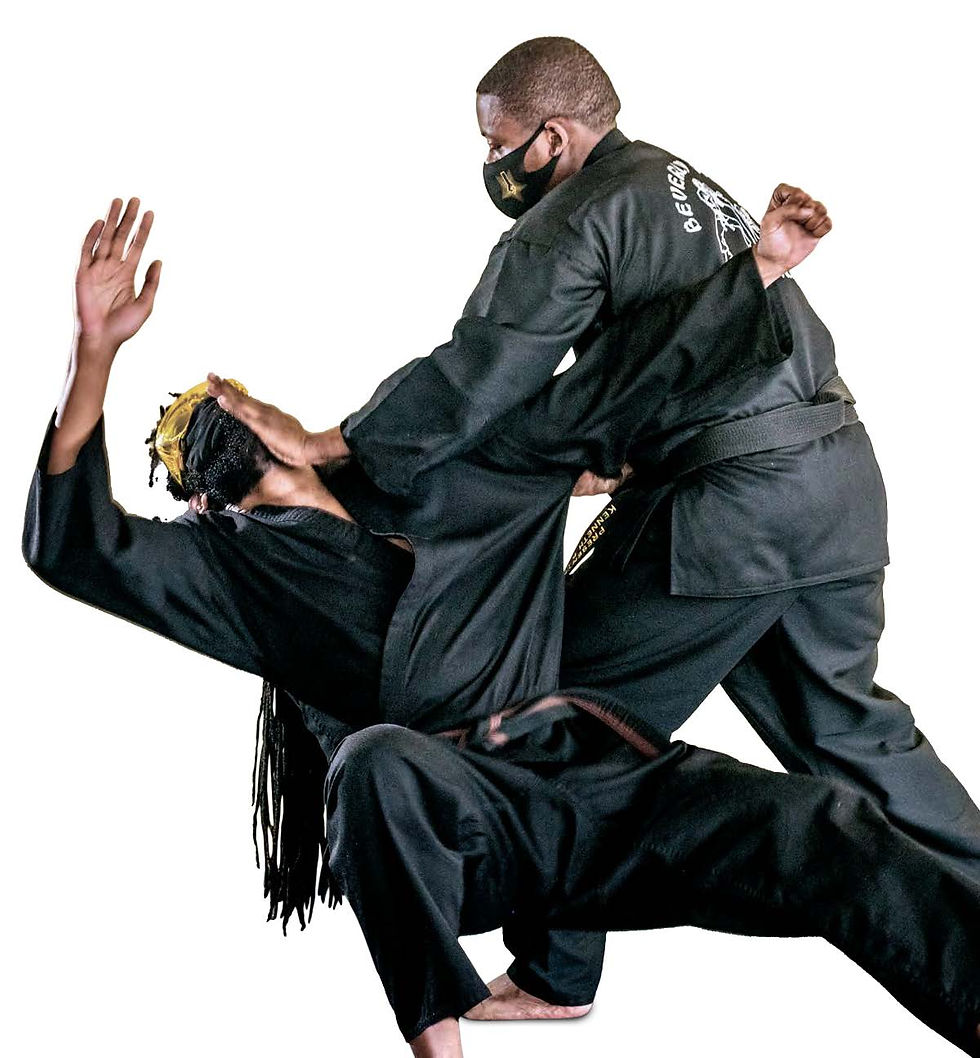

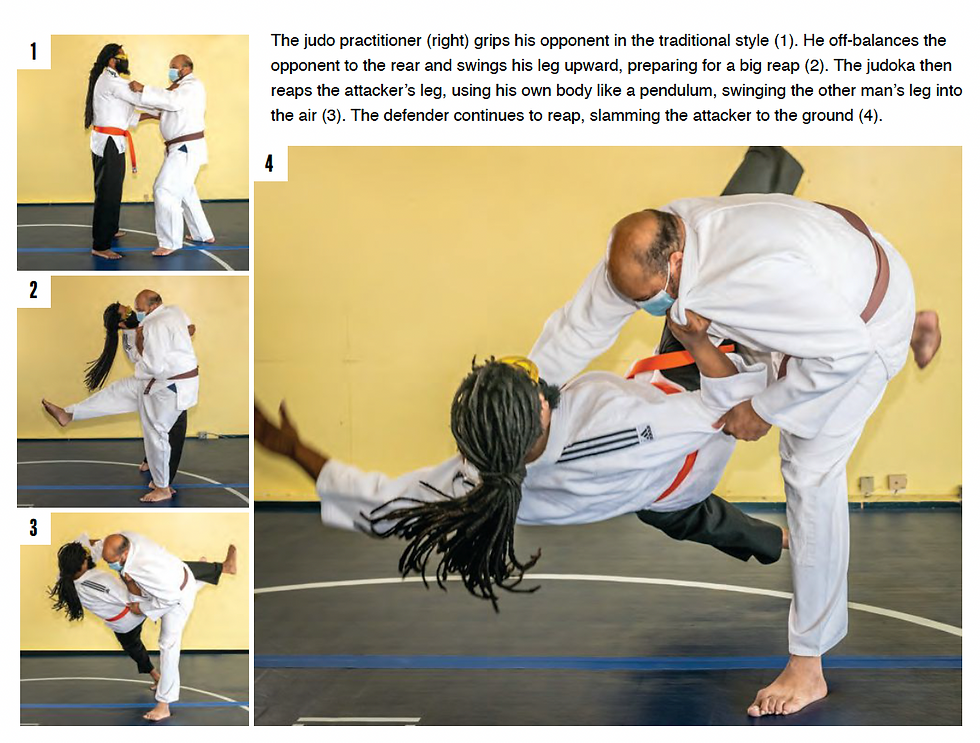

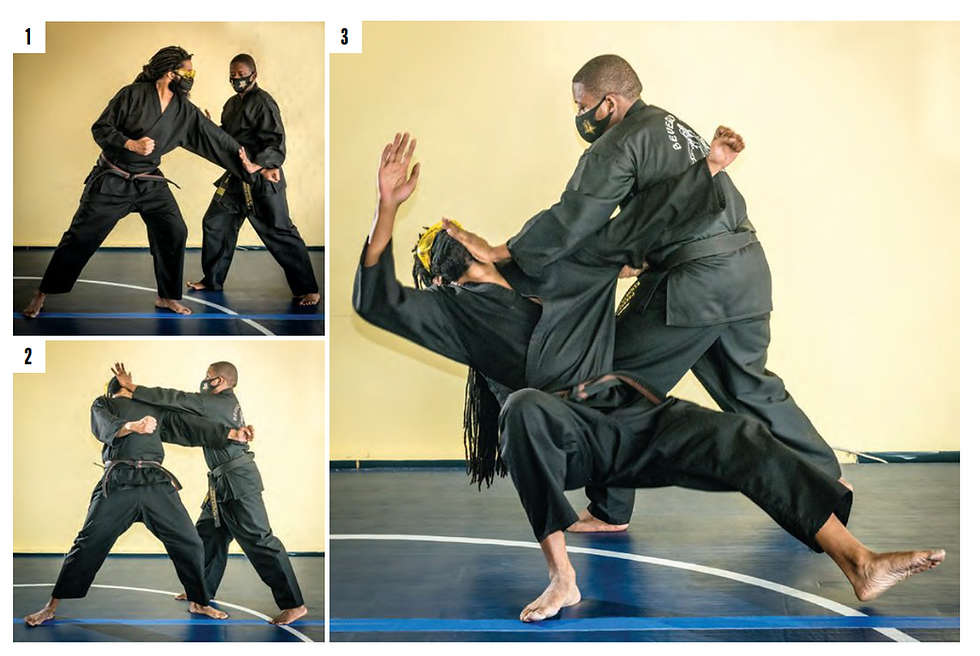

In karate, this throw looks closer to osoto otoshi. This version of the throw, also known as major outer drop, is used in judo when osoto gari is resisted. When the opponent tries to stiffen his leg to resist the throw, you slide your calf across the back of his thigh, slicing downward and using your leg like a fulcrum to drop him to the ground. In karate, maintaining one’s balance is paramount, so the fully committed version of the throw is not optimal.

After the initial exchange, in which the karateka takes the opponent down, the aim is not to initiate grappling but to put the opponent in a position primed for a strike. At the end of the technique, you end up in a position similar to zenkutsu dachi, ready to add a finishing punch or stomp to the face or ribs.

Executed Effectively

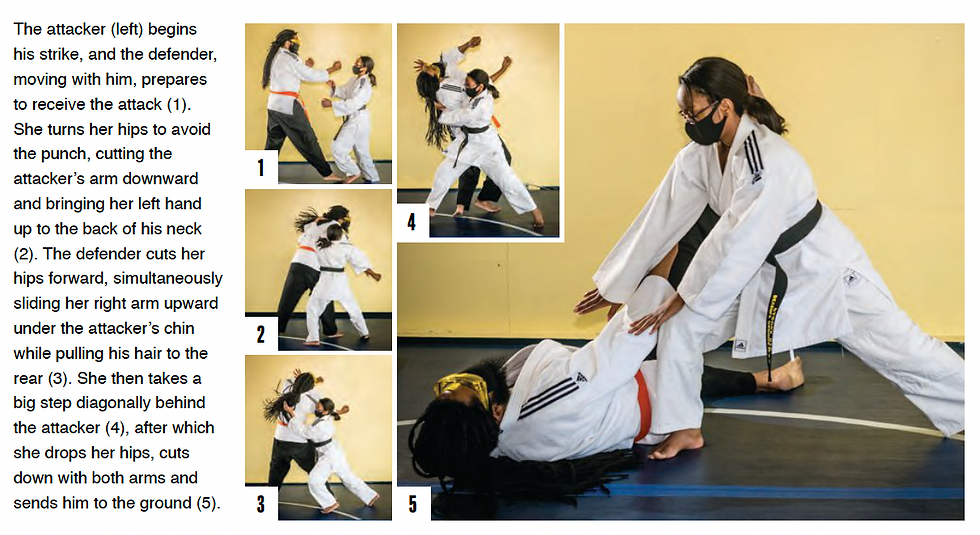

In aikido, one of the first throws taught is shomen irimi nage. When your opponent attacks, you spin on your body’s vertical axis andredirect the attack downward. Then, as he is overextended forward, your arm cuts circularly upward under his chin and, following a forward step diagonally behind him, you drop your hips and take him to the ground.

In karate, a similar technique starts almost the same. The attacker punches, and you step back and redirect the punch downward. This time, however, you step forward and simultaneously attack his chin with a palm strike, continuing forward to force his head and body backward and to the ground.

Even something as simple as a sweep can be drastically different in hard and soft styles. In judo’s de ashi barai, the basic sweep is gentle and depends on timing and finesse. In contrast, a sweep from shotokan karate is little more than a roundhouse kick to the calf that knocks the opponent off his feet. This isn’t to say that karate lacks finesse — far from it — but in application, it’s advantageous to make one technique similar to another that has already been mastered.

The primary tool of hard styles is striking, and it makes sense that practitioners would use grappling techniques to set up strikesand kicks. Using grappling in this way supports the hard stylist’s primary weapon. To try to use grappling the same way as a soft stylist is a mistake, and a dangerous one. Grappling is a supplement, not a replacement.

With an Open Mind

The same is true for soft stylists. Since arts like judo, aikido and Brazilian jiu-jitsu emphasize throws and grappling techniques, strikes are best used to off-balance the opponent. Take the simple front kick.

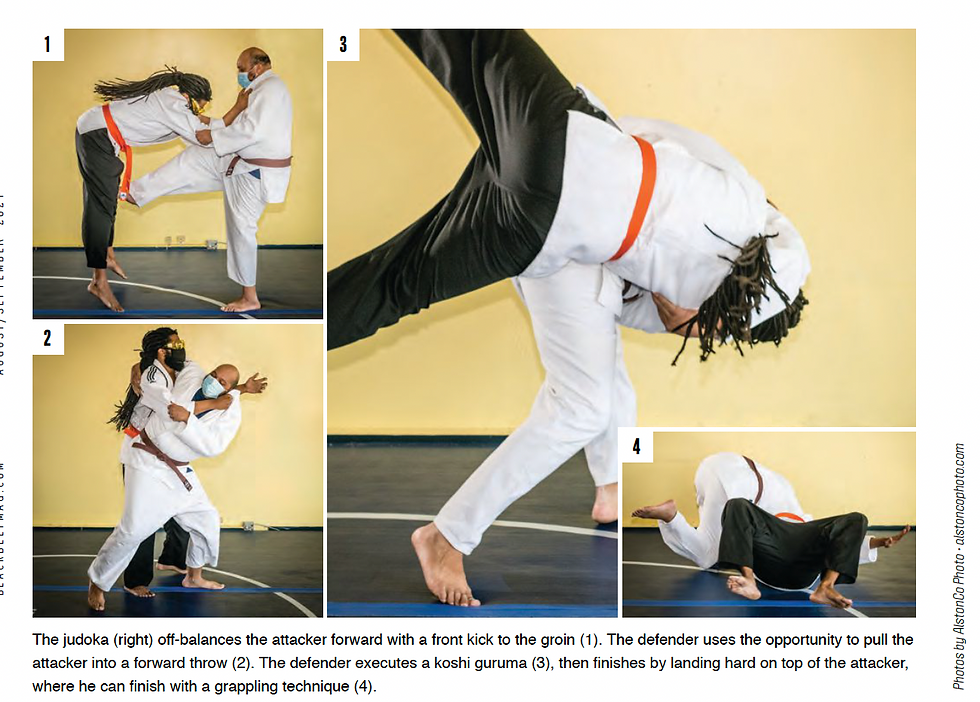

The most basic leg technique, a front kick to the groin distracts and off-balances the opponent in front, whereas the judoka can effect a throw such as harai goshi or koshi guruma. Again, following the goal of doing the most damage possible with the throw, once the defender has rotated the opponent over his hips, he can follow the momentum, continuing to the ground and landing on the attacker’s rib cage with all his weight.

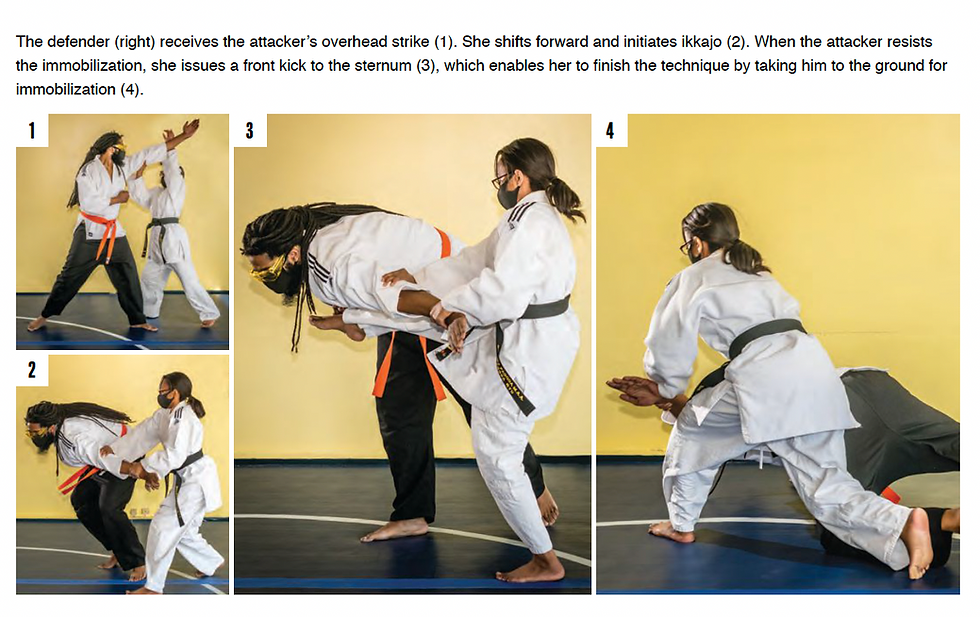

The kick is just as useful in aikido. After receiving an overhead strike and continuing into ikkajo, the attacker often resists. This could be a result of bad timing on the defender’s part or an experienced attacker anticipating the technique. Either way, when the attacker resists a well-placed front kick to the ribs, it can make all the difference, allowing the defender to complete the immobilization.

Another technique for setting up throws is the elbow strike. After blocking an opponent’s attack, the judoka can slam a horizontal elbow into the jaw, sending the opponent backward. Then it would be a simple matter of continuing forward and sending him flying with osoto gari or a double-leg takedown.

As mentioned before, aikido has been an easy and regular target for ridicule and debate for its seeming lack of realistic fighting techniques. One of the major criticisms is the almost complete lack of strikes and kicks in the art. This is untrue. Aikido has a rich cache of striking techniques to complement its throws and immobilizations.

These elements have been ingrained in the art from the beginning. In Budo: Teachings of the Founder of Aikido, which collects some of the earliest photos from Morihei Ueshiba’s development of aikido, the evidence supports this. Taken at the infamous Noma Dojo, at first glance many of the techniques look like run-of-the-mill aikido that you’d see at any modern school. Until you look closer. O-Sensei’s descriptions of the techniques paint a different picture than one sees in the modern-day variants. A technique like sokumen irimi nage (a version of shomen irimi nage in which the defender throws the attacker from the side), for example, is more than what it seems. When the defender in the modern version executes the throw, one arm slides to the base of the attacker’s throat and the other to just in front of his torso. From here, the defender extends forward, drops his weight and throws the attacker. In Budo, the photos show much the same, but the text describes the defender using both arms to strike the attacker’s throat and ribs.

To Achieve the Goal

When you focus on these aspects of your traditional style, whether hard or soft, it will only strengthen your technique. Furthermore, it will make transitioning to the other end of the spectrum smoother. The lines between hard and soft begin to meld together when you fine-tune those parts of your traditional practice.

Thanks to the rise of the mixed martial arts, traditional stylists often feel obligated to cross-train. This is generally a good thing. It’s important to remember, however, that the rudiments of both hard and soft techniques can be found in your own traditional art. Master those techniques, and a world of possibilities will open for you.

Marcus Day has practiced martial arts for 24 years. A fourth-degree black belt in the pagoda ryu karate system, he teaches at Beverly Pagoda Martial Arts Academy in Chicago. For more information, visit beverlypagodamartialartsacademy.com or marcusday.org.

This article originally appeared in a 2021 edition of Black Belt Magazine.