Inside Goju-Ryu

- Black Belt Team

- Feb 10, 2024

- 7 min read

by Don Warrener

Photos by Rick Hustead

Ever since 1945, Okinawa, a tiny island in the Pacific, has been familiar to Westerners, especially those who are into the martial arts. Ravaged for centuries by the Japanese, it was the site of the infamous Battle of Okinawa near the end of World War II. The United States government estimated the death toll at 35,000 American soldiers, 90,401 Japanese soldiers and 62,489 civilians.

But this article is not supposed to be a history lesson—at least, not one that reaches back quite that far. Rather, it’s intended to offer a glimpse inside Okinawan goju-ryu karate, one of the arts that has thrust the island into the limelight in recent years. To get a true picture of the way things used to be and how that determined the way things are, there’s no better source than the man who’s in the cross hairs of much of the controversy: Teruo Chinen.

Chinen initiated his martial education under one of the two giants of Okinawan karate, Chojun Miyagi. (The other giant, of course, was Gichin Funakoshi.) Chinen started training in 1950 when his uncle decided he needed a dose of discipline after he brought home a disappointing report card from school. He often speaks of his run-ins with Miyagi, who had him yanking weeds from the bottom of the makiwara posts in the Garden Dojo during one of his first lessons.

But Chinen claims he didn’t really learn his karate from Miyagi. Instead, he picked it up from the police officer who was in charge of cleaning up the dojo after a hurricane struck the island—none other than Eiichi Miyazato, the man who inherited the seeds of goju-ryu. —D.W.

Black Belt: Please tell us of your memories of Eiichi Miyazato.

Teruo Chinen: Miyazato Sensei was one of the most impressive people I ever met. He was wonderful, kind, talented, knowledgeable and the one to whom I credit my learning.

BB: What were those early days like?

Chinen: When we moved to the Jundokan in Okinawa, where the dojo now stands, it was I who moved the makiwara (punching posts), the chi ishi (strength stones) and the kongo ken (iron rings) from Miyagi Sensei’s Garden Dojo. Along with my friends, we carried them on our shoulders. It was nothing at the time to us, but now when I look back, it was a very significant thing we did. This is why I call them the seeds of goju, as it is these training devices that have helped so many develop their talents in goju. This was a real honor.

Demo 1: The opponent bear-hugs Teruo Chinen from behind (1). The goju-ryu master repositions

his right leg between the assailant’s legs and bends forward (2), then grabs his pant legs

and lifts (3-4). The opponent is slammed to the floor (5).

BB: Do you consider Miyagi’s uniform and belt to be the symbols that signify who the inheritor of goju is?

Chinen: I guess that depends on whom you talk to, but for me, it is the seeds that are the important items, not the flower which is Miyagi Sensei’s gi. This is only the flower, and in time this will be gone, but the seeds will fertilize and grow more seeds. This is why I feel the seeds are the important part of goju. Personally, I believe that the uniform, which was given [to his student, Meitoku Yagi] by his family years after the master’s death, should be put in the Okinawa Museum and not in someone’s dojo

for only a few to look at.

BB: Why do you have kumite (sparring) in your Okinawan goju while none of the schools on the island, including the famous Jundokan, teaches it?

Chinen: When I moved to Tokyo and became an assistant instructor at the Yoyogi Dojo, my sempai, Morio Higaonna, decided that after watching kumite contests, we needed to learn this aspect of goju. We needed to incorporate it into our goju if we were to be complete. So that is exactly what we did, but we did not change or let up our training in kata. We just trained harder.

BB: What was the effect of incorporating kumite into your training?

Chinen: I think it is one of the best things the Japanese have given to our Okinawan art of goju and something we should be very grateful for. The Goju Kai tournaments we saw really impressed us with the kumite, and there were several foreigners there at that time as well. Peter Urban had a group from New York, and this also impressed me.

BB: You mentioned that you never abandoned your emphasis on kata. How can a person study only a few of them for a lifetime without getting bored?

Chinen: Goju is different from other styles that have so many kata in that goju is a deep style and not a wide style. When I say deep, I mean that the moves in the kata are deep. To totally understand one move can take years and years, as there are so many variables to each one. And these moves that we call bunkai oyo are the study of the [techniques] in the kata—they can take a lifetime to learn.

Demo 2: Teruo Chinen (right) faces his partner (1). When the man punches, Chinen moves off the line of attack and traps his arm (2). He then places his right leg across the front of the partner’s torso while maintaining his hold on the arm (3). Next, Chinen places his left leg behind the man’s legs to effect a leg-scissor takedown (4). To finish, he raises his right leg (5) and strikes downward with a heel kick (6).

BB: Can you give an example?

Chinen: If you show the opening move of the kata sepai to the non-practitioner, it is hard for him to visualize the meaning. But if you take a look at another style’s kata, it is easy to understand a high block and what it is for. To understand the opening move of sepai is very difficult, and I am still learning new applications for it all the time.

BB: In classical Okinawan goju, why have weapons never been taught?

Chinen: If I may correct you a little, there was actually kobudo taught as part of the classes. Miyazato Sensei invited Taira Shinken to our dojo, and one day he showed up and began teaching kobudo. I remember him coming through the door with a huge box on one shoulder and a bundle of bo on the other shoulder. We practiced kobudo with Taira Sensei. You are right in that it is not part of the regular training, but Miyazato Sensei did organize the kobudo training at our dojo. My family also practiced yamani-ryu kobudo, so I practiced all the weapons—bo, sai and tonfa— quite a bit when I was younger.

BB: Your training is like sanchin in that you’ve faced three battles: your early training in Okinawa, your experiences in Tokyo at the Yoyogi Dojo, and your teaching and training in Washington. How did they differ, and what was the greatest benefit from each?

Chinen: When I was training in Okinawa, I was very young. I went to Tokyo when I was around 20 years old. My priority was to train at the Yoyogi Dojo, and that took up much of my time. The training was the best, as my sempai and I had to train on our own and not in classes with Miyazato Sensei like we had the honor of when we were in Naha. So this time in Tokyo was very important in my life [because] I developed much of my skills.

In fact, I never owned a karate gi until I moved to Tokyo and my sempai bought me a Tokaido gi. This is a very good memory. Then, in 1969, I was supposed to go to Sao Paolo, Brazil, to teach, but I changed [my mind] and came to Spokane, Washington, where I live today. This is where I started to develop my own students, and I am very proud of how talented many of them have become. I also started my own organization: Jundokan International.

BB: While watching your most recent DVD set, I noticed that you covered many areas, from basics to bunkai oyo to kumite to self-defense. Why did you put so much into this project?

Chinen: Well, I saw a DVD of Kyuzo Mifune the night before we started shooting the project. He was over 70 years old when he did it and truly one of the legends of judo, a 10th dan from the Kodokan. This inspired me to pull out all stops and give this project 110-percent effort. I hope that people who purchase these DVDs will be educated by them.

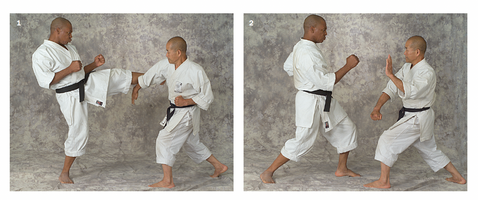

Demo 3: When his adversary kicks, Teruo Chinen parries the blow with his right arm (1). The

opponent resets (2) and punches, causing Chinen to redirect the limb with his left hand (3). He immediately turns and drops to his left knee (4), then executes a low kick to the man’s lead leg (5). As soon as he hits the floor (6), the goju-ryu master strikes his neck and controls him (7-8).

BB: Your dojo kun (set of school precepts) is composed of eight parts. Can you elaborate on them?

Chinen: Well, these are the words of Miyagi Sensei. Miyazato Sensei formalized them after the master passed away, and I now use them as our dojo kun. I think these are the ideals of what a goju practitioner should strive for in his or her own life:

• Be humble and polite.

• Train considering your physical strength.

• Practice earnestly with creativity.

• Be calm and swift.

• Take care of your health.

• Live a plain life.

• Do not be too proud or modest.

• Continue your training with patience.

BB: Is there anything else you would say to the readers of Black Belt?

Chinen: I would only say to them, don’t be a window shopper. By this, I mean do not change your sensei at the drop of a hat. Stay with one sensei for your lifetime and learn from him. I believe I am a good example of this as I have had only one sensei, Eiichi Miyazato, for my entire life. He was the best. It may sound prejudiced, but this is why I believe he is the inheritor of Okinawan goju.

About the author: Don Warrener is the president of Rising Sun Productions, a company that produces martial arts videos and DVDs. To contact him, write to 628 North Doheny Drive, Los Angeles, California 90069. Or send e-mail to donrw@earthlink.net.

This article originally appeared in a print edition of Black Belt Magazine.