- Apr 16, 2024

- 9 min read

“Jeet Kune Do is simply the direct expression of one's feelings with the minimum of movements and energy.”

BRUCE LEE, that five-foot-eight-inch-145-pound cache of Chinese TNT who plays Kato, the crime- buster in TVs "Green Hornet," is a stickler for realism.

If a TV producer asks him to play a role, Bruce now wants to know before he signs up whether the part is reasonably realistic.

The dynamic, effervescent plague of the TV hoodlums, let the bars down a wee bit when he accepted the role of bodyguard and faithful companion to "The Green Hornet'' by hoaxing up his gung-fu tactics to provide more exciting action.

But the San Francisco-born, Hong Kong-raised actor has learned some valuable lessons from his initial experience in the world of make-believe.

Millions of kids were thrilled by Kato and "The Green Hornet" as they went about stamping out crime and corruption in their forceful manner. But the older viewers looked at the show with a fishy eye because the idea of two crime crusaders wearing black masks didn't appeal to their believability.

However, the show has lost none of its appeal to the small fry and is enjoying re-runs here and abroad, but Bruce hopes to reach all ages with more plausible plots.

And it'll figure prominently in his thinking when he considers his next TV role. "Some time ago I was offered a No. 1 spot in a proposed one-hour series titled, 'Number One Son' (Son of Charlie Chan) and it was going to be like a Chinese James Bond type of thing," Bruce related in an interview with Black Belt Magazine.

"I wanted to make sure before I signed that there wouldn't be any 'ah-so's' and 'chop-chops' in the dialogue and that I would not be required to go bouncing around with a pigtail."

The deal never did materialize but Bruce had the inner satisfaction of knowing that he wasn't about to submit to movie stereotypes and that he would never do anything that might degrade the Oriental race from which he springs.

And when it comes to Chinese gung-fu, Bruce also insists on realism and plausibility. There are many different schools of gung-fu in China, according to Bruce, and like in the United States, it is difficult to find worthwhile instruction.

"Too much horsing around with unrealistic stances and classic forms and rituals," says Bruce. "It's just too artificial and mechanical and doesn't really prepare a student for actual combat. A guy could get clobbered while getting into his classical mess. Classical methods like these, which I consider a form of paralysis, only solidify and condition what was once fluid. Their practitioners are merely blindly rehearsing systematic routines and stunts that will lead to nowhere."

Bruce characterizes this type of teaching as nothing more than "organized despair."

Basically, his technique is to proceed instantly and unceremoniously to knock his adversary flat on his wallet before he can even remember why he picked on him in the first place. Lightning movements play an important part in Bruce's techniques. To perfec his speed, Bruce has developed an extraordinarily quick eye and uncanny fast hands.

Standing back a few feet, he can grab a dime right out of your palm before you can close your hand. He demonstrated that maneuver to this reporter and left a penny clutched in our hand in exchange for the dime, a switch he executed so swiftly it almost seemed magical.

As is obvious by now, this buoyant, 26-year-old expert in the Chinese art of gung-fu (bis Chinese name is Lee Jun Fan) takes a dim view of the classical versions of this ancient martial art.

"To me, a lot of this fancy stuff is not fμnctional," he says and he tries to prove it through the three gung-fu kwoons (schools) he operates in Seattle, Oakland and in Los Angeles, Chinatown. All feature Jeet Kune Do, Chinese boxing. He calls his establishments the "Jun Fan Cung Fu Institute." Because they are "exclusive" establishments, none bear any commercial signs on the outside to identify it. However, as Bruce points out, "The 'in groups' know where they are.

Bruce doesn't teach publicly. His students are carefully chosen. These are mostly instructors of different styles and they take instruction at these kwoons once a week. Occasionally, when he feels up to it, Bruce teaches private lessons, ranging from $27.50 to $50 an hour, and some of his private students fly in all the way from the East Coast.

"These private lessons are usually not interesting," Bruce relates. "It is more enjoyable to teach those who have gone through conventional training. They understand and appreciate what I have to offer. When I find an interesting and potential prospect, I don't charge him a cent."

A Memorial

To get a closer look at Bruce Lee's techniques, the Black Belt Magazine reporter visited his kwoon in Los Angeles' Chinatown and immediately got the message as he stepped through the front door. Near the entrance his eyes fell on a miniature tombstone embellished with a bouquet of flowers.

Inscribed on the tombstone were these cryptic words: "In memory of a once fluid man, crammed and distorted by the classical mess."

“That expresses my feelings perfectly," Bruce explained as he stripped down to his undershirt and trousers and went into a two-hour practice session with Daniel Lee, a friend and stalwart adherent of Bruce's Chinese techniques in Jeet Kune Do.

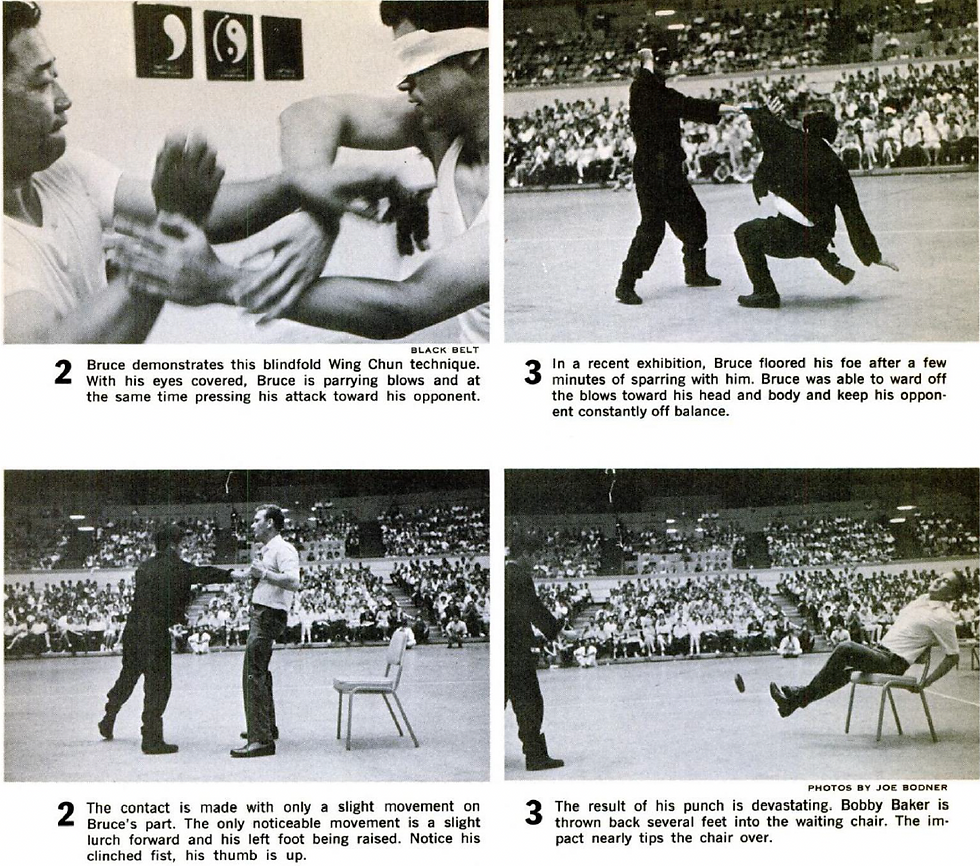

As Black Belt photographer Oliver Pang focused his camera on the action, we watched Kato of TV fame move about the kwoon like a panther, counter-attacking, moving in, punching with great power from the hips. Occasionally, shin kicks, finger-jabs, powerful body punches to the solar-plexus, use of elbows and knees. We noted that Bruce's body was constantly relaxed.

The movements are like those of a polished, highly-refined prizefighter delivering his blows with subtle economy. There seems to be a mixture of western fencing and the Wing Chun style wrapped up in Bruce Lee's techniques of Chinese gungfu.

Yet, his Jeet Kune Do is unlike any existing style. During the workout with Daniel Lee, Bruce, showing hardly a sign of hard breathing, would pause to explain to this reporter what Jeet Kune Do is all about. It is quite different from the classical gung-fu.

As Bruce himself describes it:

"The extraordinary part of it lies in its simplicity. Every movement in Jeet Kune Do is being so of itself. There is nothing artificial about it. I always believe that the easy way is the right way Jeet Kune Do is simply the direct expression of one's feelings with the minimum of movements and

energy. The closer to the true way of gung-fu, the less wastage of expression there is.

"There is no mystery about my style. My movements are simple, direct and non-classical. Before I discuss Jeet Kune Do, I would like to stress the fact that though my present style is more totally alive and efficient, I owe my achievement to my previous training in the Wing Chun style, a great style. It was taught to me by Mr. Yip Man, present leader of the Wing Chun Clan in Hong Kong where I was reared.

"Jeet Kune Do is the only non-classical style of Chinese gung-fu in existence today. It is simple in its execution, although not so simple to explain. Jeet means 'to stop, to stalk, to intercept' while Kune means 'fist or style' and Do means 'the way or the ultimate reality.'

''In other words, 'The Way Of The Stopping Fist.' The main characteristic of this style is the absence of the usual classical passive blocking. Blocking is the least efficient. Jeet Kune Do is offensive, it's alive and it's free.

Bruce also points out, and with great emphasis, that there are no classical forms or sets in the system because they tend to be rhythmic. He likes broken rhythm and says "classical forms are futile attempts to 'arrest' and 'fix' the ever-changing movements in combat and to dissect and analyze them like a corpse.

What he is dealing with, explains Bruce, is "the actual reality of combat," with none of the abstractions that set up a simulated exchange, resembling anything from acrobatics to modern dancing ...

"When in actual combat," Bruce stresses, "you're not fighting a corpse. Your opponent is a living, moving object who is not in a fixed position, but fluid and alive. Deal with him realistically, not as though you're fighting a robot."

Unlike other styles that practice in rhythm, which Bruce calls "two-men cooperation," Jeet Kune Do uses broken rhythm in both training and sparring.

As we watched Bruce through his workouts, we became intrigued by his continual emphasis on "non-classicism," directness and his insistence on simplicity.

"Can you explain just what you mean when you say, 'being non-classical?' " we asked.

"Traditionally, classical form and efficiency are both equally important," Bruce declared. "I'm not saying form is not important, economy of form that is, but to me, efficiency is anything that scores.

"To illustrate my point, let me tell you a story: Two Orientals were watching the Olympic Games in Rome. One of the chief attractions was Bob Hayes, the sprinter, in the 100-yard run. As the gun went off to set the race in motion, the spectators leaned forward in their seats tense with excitement.

With the runners nearing their goal, Hayes forged ahead and flashed across the line, the winner with a new world's record of 9.1 seconds.

"As the crowd cheered, one of the Orientals elbowed the other in the ribs and whispered, 'Did you see that? His heel was up.”

"You don't have to hit us over the head - we get the point," we said. "What then do you mean when you say,''directness?' .. We had hardly gotten the words out of our mouth when Bruce's wallet came flying at us. Automatically, we reached up and grabbed it in mid-air. •

Comes Naturally

When we regained our composure at Bruce's sudden move, Bruce said:

"That's directness. You did what comes naturally. You didn't waste time. You just reached up and caught the wallet and you didn't squat, grunt or go into a horse stance or embark on some such classical move before reaching out for the wallet. You wouldn't have caught it if you had."

Bruce paused a moment and continued:

"In other words, when someone grabs you, punch him! Don't indulge in any unnecessary, sophisticated moves! You'll get clobbered if you do and in a street fight, you'll have your shirt ripped off of you."

"All right, Bruce," said, warming to the subject. "Now we understand what you mean ,when you speak of 'directness.' Now, let's elaborate a little on the last of the three essentials of Jeet Kune Do - 'simplicity.' "

"The best illustration is something I borrowed from Ch'an (Zen)," Bruce began. "Before I studied the art, a punch to me was just like a punch, a kick just like a kick. After I learned the art, a punch is no longer a punch, a kick no longer a kick. Now that I've understood the art, a punch is just like a punch, a kick just like a kick.’

"The height of cultivation is really nothing special. It is merely simplicity, the ability to express the utmost with the minimum. It is the halfway cultivation that leads to ornamentation."

Bruce laid emphasis on the fact that adherents of Jeet Kune Do do not indulge themselves with fancy embellishment.

"It is basically a sophisticated fighting style stripped to its essentials," Bruce explained. "The disciples are very proud to be accepted in this exclusive style."

The actor-gung-fu expert stressed over and over again that he doesn't believe in loading up his techniques with all sorts of "superficialities," as he calls them. He likes to compare his art to the work of a sculptor.

"In building a statue," Bruce said, "a sculptor doesn't keep adding clay to his subject. Actually, he keeps chiseling away at the unessentials until the truth of his creation is revealed without obstructions.

"Thus, contrary to other styles, being wise in Jeet Kune Do doesn't mean adding more. It means to minimize. In other words, to hack away the unessentials. It is not a 'daily increase' but a 'daily decrease.' The way of Jeet Kune Do is a shedding process.

"In short, Jeet Kune Do is satisfied with one's bare hands, without the fancy decoration of colorful gloves which hinder the natural function of the hand."

Bruce Lee studied philosophy at Washington University and he is an avid student of Zen, Taoism and Christianity. And when the time is appropriate he will philosophize.

"Art," he observed, "is really the expression of the self. The more complicated and restricted the method, the less the opportunity for the expression of one's original sense of freedom.

"Though they play an important role in the early stage, the techniques should not be too mechanical, complex or restrictive. If we blindly cling to them, we will eventually become bound by their limitations.”

To be continued...