- Benjamin Dearman + Christopher S. Spaulding

- Nov 12, 2024

- 8 min read

Updated: Nov 15, 2024

In all likelihood, I look at martial arts and self-defense training differently than you do.

Yes, I’m an avid practitioner, as well as an instructor. However, I also have hands-on knowledge gained while training special operators — on base, five hours a day, every day — for a year. And I coached the 3rd Ranger Battalion, leading them to the first All-Army Combatives Championship.

Please don’t envision any of this as a Rambo fantasy. My work involved training people who risk their lives to keep America safe and free. Therefore, what I taught them had to be effective. BS is not tolerated when so much is at stake.

I’m also an exercise scientist, a biomechanics specialist and a certified strength-and-conditioning coach. As you might guess, martial arts training is my life. I take it seriously, and I think you do, too. So pull up a chair and take out your notebook to capture these notes on the science of self-defense.

You’re about to learn what America’s elite fighters are taught.

The Principle

My time as a martial arts instructor and trainer has given me a unique perspective on a concept I refer to simply as “push and pull.” The ability to properly perform these two fundamental movements in the gym, in the ring and on the street is vital for any martial artist. The following are some key “exercises” — and I use that term loosely because technically they are movements.

If you’re not already doing these exercises, you should be. If you’re already doing them, by the time you finish this article, you’ll have some new ways to tweak them to maximize their effectiveness.

The movement is formally called a “push-pull,” but you may know it as a punch, a grab, a pull, a push, a transition or an opening.

Picture this: You’re walking down the street, minding your own business, and wham! Some thug pushes you up against the wall. You don’t know why he’s doing it or what his motives are, but you do know he’s got bad intentions, and your only way out is blocked.

Your self-“offense” training instantly kicks in. You grab the aggressor’s left upper-pectoral insertion (or shoulder) with your right hand and brace his right elbow/shoulder with your left hand. Then you simultaneously push with your right hand, pull with your left and step to your right while making a 180-degree turn and slamming his back into the wall.

Congratulations! You just executed a beautiful push-pull, a transition from a defensive position to an offensive position.

Here’s another scenario: You’re caught flat-footed by someone with a knife who’s demanding your money. All of a sudden, he thrusts the blade at you. You swing your right hand down and into the back of his right hand. Grabbing that hand with yours, you pull him into you while delivering a fist or elbow to the face. Push-pull.

And yet another: You’re in the dojo, working on your jab-cross combination. You snap out your left hand in the form of a jab, then pop out a right cross. Ever seen a newbie throw that combination and compared it to the way an experienced fighter does? The noob looks like he’s punching while holding onto elastic straps, while the elite fighter looks like his punches are being launched crisply from the hips. They snap like a bullwhip.

That launching from the hips happens because the martial artist pushes his left hand away from his body. Midway through that movement, his hips are already starting to counter-rotate to pull the jab back and transition to the cross. A classic push-pull. If he didn’t do that, the force he generated would propel him forward and disrupt his balance.

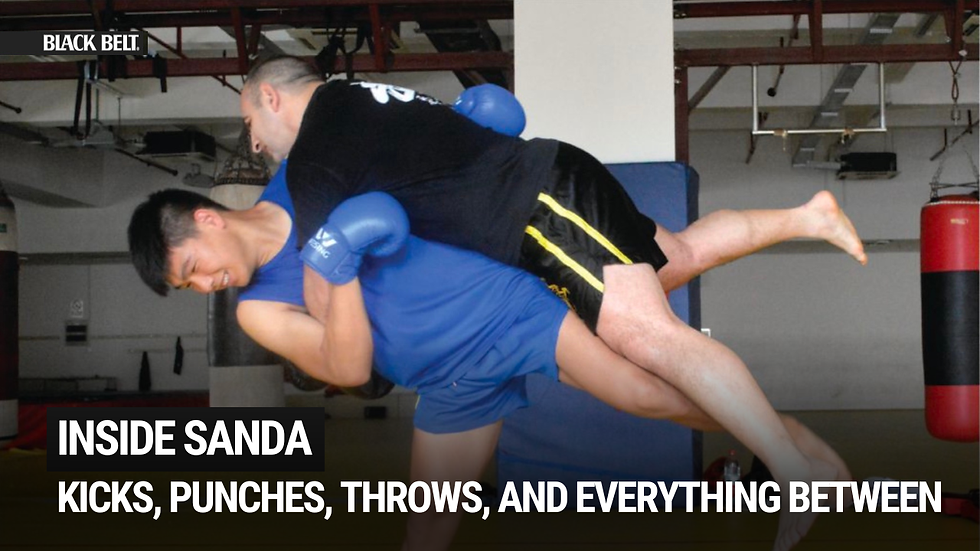

In grappling, the push-pull is sometimes called “creating an opening” or “off-balancing your opponent.” This is accomplished by having at least three points of contact: pushing on one point, pulling on another point and having a third to serve as a stable base. This instinctive push-pull combination forces your opponent’s body to react in a predictable manner that creates an opening you can capitalize on — perhaps by transitioning to a throw, strike or finishing technique.

The Science

This section delves a bit into kinesiology. Even if you don’t know much about that field, stay with me. Consider how you move your body in terms of unilateral, or one-sided, activities. Think of punching and kicking compared to swinging a baseball bat or rowing a boat.

Punching and kicking involve the use of one extremity, primarily to deliver force. A bilateral activity uses two limbs in conjunction to allow and encourage the transfer of force from one area of the body to another area of the body or into an external object.

Now, your body is well-designed to control, buffer and dissipate rotational forces such as those generated in such movements. Think of running. When your right knee is raised, your right arm swings behind your torso and your left arm rises in front.

Why not run with your right knee up and your right hand up?

First, you’d look ridiculous.

Second, you’d spin around from the force you’re generating.

The choice isn’t whether to do a push-pull; the choice is how to best train for it and how to strengthen the associated mechanics in the gym.

The Benefits

No. 1

Striking noobs typically don’t use their hips efficiently.

Often, they don’t use any part of their body well — except, of course, their face. For some reason, a beginner’s face is really good at stopping punches. I speak from my own experiences from back in the day.

Novices tend to use their hips in excess, which generates too much rotation when they strike. And since their core is poor at transferring that force into their thoracic spine and out through their hands, they may have subpar technique, exhibit poor mechanics and, even worse, telegraph. (Nothing sucks more than missing your opponent with a punch, only to wake up on the floor, wondering what happened.)

Most of the force beginners generate is wasted because they’re not yet efficient at striking — or kicking, for that matter.

In contrast, when you look at professional fighters, you see people who have managed to distill their telegraphing down to such minuscule movements that they can be noticed only by other experienced fighters. Their punch starts with their hips. (Actually, it starts with the big toe, but that’s another article.)

Too much rotation results in sloppy punching and telegraphing. Too little rotation yields tired arms. The push-pull concept trains the body to move the hips subtly. Often, beginners have an issue with this because they’re not used to generating power without pushing that power into something.

The take-away: Push-pull trains the hips to work with the shoulders.

No. 2

When you throw a jab, your body seemingly wants to follow up with a kick or punch from the opposite side. A left jab with a right cross flows more smoothly than a left jab coupled with a left hook.

When you throw left-left, there’s a reset that must happen. When you throw left-right, the need for a reset is gone and the transition of force is amplified. The push-pull movement helps you develop that reactive sequence that your body wants to do.

The take-away: Push-pull builds on and enhances natural tendencies and movements.

No. 3

The push-pull movement trains the core the same way you want it to work when you strike (with the exception of knees and down elbows) and when you engage in stand-up grappling. By practicing push-pull, you’re teaching your body to work as a unit while you’re standing, which has a strong carry-over to stand-up fighting.

It’s called “functional training.” I hear a few books have been written on the subject.

The take-away: Push-pull trains the core in a very functional way.

No. 4

When you learn to do anything, your body creates neural “highways” that connect your brain with specific muscles and groups of muscles. Just as the creation of a real highway takes time, so does the creation of a neural highway. Both allow one thing: a quicker delivery (or path) to a desired destination (or outcome).

Unless you’re a grappler, you shouldn’t be on your back pushing a weight away from you in the gym. That amounts to creating a highway for vehicles we don’t have — like flying cars. As silly as that sounds, it’s a good analogy.

Bench-pressing and the push in the push-pull are similar. The difference is that with the proper exercise movement, your whole body is engaged in the push-pull the same way you’re going to fight — that is, standing.

The take-away: The push-pull helps strengthen punching and enhance the motor patterns associated with it.

Consider: You often have to consciously control the counter-rotation that results from a punch or kick if you don’t take that momentum into another strike. But sometimes it’s smart not to surrender to your body’s wants. That’s where push-pull comes in. The movements will help strengthen your ability to control body rotation while training your body how it naturally wants to work — as a unit.

The Exercises

The push-pull is typically done from a bilateral stance with your feet shoulder-width apart. You’re holding a cable in your right hand that leads to a weight stack in front of you and another cable in your left hand that leads to a weight stack in back of you.

When you’re ready, simultaneously brace your core by slightly tightening it, exhale sharply, and push your right hand out while pulling your left hand back.

Hold, then slowly lower the weights to their starting position.

That’s one rep. Do all your reps on one side, switch to the other side and then rest. That’s one set.

Frequent Flaws: The first involves rotating the hips. Remember that this is not a punch; it’s a movement designed to train your muscles to work as a unit to prevent or control rotation. Your hips should move a little to initiate the exercise, but excessive hip motion will take your core out of the movement and negate many of the benefits.

Remember that highway analogy?

The state doesn’t build two highways next to each other that take you to the same place. If you practice a movement that is too similar to your sport-specific movement — like punching with dumbbells — your body actually has to develop two different ways to get the job done.

And while having two ways to get a job done might be good in another arena, it just slows everything down in a fight because your body has to decide which path to take.

The second flaw involves letting your weight be centered on your rear leg. Just like when striking, you want to keep your weight on your lead leg, with the heel of your rear foot lightly touching or slightly off the ground. This ensures that your core and hips are working effectively.

The third flaw entails excessively rotating your belly/lumbar spine/midsection. Remember that power comes from your core, not your belly.

What’s the difference? Watch a pro boxer with low body fat who doesn’t do a lot of resistance training.

You’ll notice a few things: He probably has well-developed latissimus dorsi muscles to control rotation at the hips and to aid in bringing his punches back. He probably has a six-pack because of that low body fat and a propensity to do bodyweight movements.

He probably has a muscular butt, too. All these muscles are developed by repeated striking. All of them make up your core (back muscles, abdominals and hips).

So while power comes from the core, it’s not necessarily where you think it is.

The Variations

Staggered-Stance Push-Pull: This is done from a fighting stance. Just remember the motion is not that of a punch. Therefore, you need to keep your shoulders down and your head up.

Ground-and-Pound Push-Pull: Basically, when you ground-and-pound someone, you have to hold that person down — that is, push him into the ground somehow. To that end, this exercise is done with an isometric hold in your pull hand. Really, you can argue that this movement is a push-push, and I won’t debate that here. What you need to remember, though, is that it’s a badass movement that mimics a ground-and-pound while still holding true to most of what I covered previously.

Supine Push-Pull: This is basically a push-pull exercise done while you’re lying on your back. If you do it at a gym, you might get criticized for taking up too much space, but that’s OK because you’ll look crazy doing it and people will be wondering why they didn’t think of it first. Meanwhile, you’ll be building your martial arts ability in ways they cannot imagine.