- Joe Paden

- Dec 2, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Dec 6, 2025

The Renaissance Man, Arcenio James Advincula

Arcenio James Advincula embarked on the martial path for a reason that was far from unique. Being small in stature and of interracial heritage, the youth was a frequent victim of bullying. After one serious encounter with a group of young thugs, his father hired two former Filipino army scouts to school him in combat judo and escrima.

Most styles of escrima emphasize stick fighting, but the soldiers chose a different tactic: They trained young Advincula with tools that would send modern parents running out of the dojo. Specifically, they had the 8-year-old wielding a bayonet and a butcher’s knife.

Another unique aspect of Advincula’s martial education pertained to the role of the hands in combat. Many instructors refer to the non-weapon-bearing appendage as the “alive hand” and use it mainly to parry attacks, but Advincula’s teachers called it the “sacrifice hand” in honor of its special purpose in a fight. Yes, it was used for parrying, but it was also subject to being sacrificed to forestall a cut or stab aimed at a vital organ.

Martial Artist

Advincula joined the U.S. Marine Corps in 1957 and a year later found himself stationed on the “island of karate,” aka Okinawa. On December 1, 1958, he first set foot inside the dojo of the legendary Tatsuo Shimabuku, thus beginning his study of isshin-ryu and kobudo.

Shimabuku had created isshin-ryu by combining elements he’d learned from Chotoku Kyan and Choki Motobu, who taught shorin-ryu, with what he gleaned from his time with Chojun Miyagi, founder of goju-ryu. To that mix, Shimabuku added his own innovations and concepts, giving birth to a unique martial art. A quick study, Advincula became one of Shimabuku’s top students.

Standing 5 feet 6 inches tall and weighing 150 pounds, Advincula possessed a stature that was similar to that of his isshin-ryu teacher. Kyan, Shimabuku’s most influential sensei, was also very small, but he was renowned for his speed and maneuverability — attributes he strove to pass down to Shimabuku and, by extension, to Advincula.

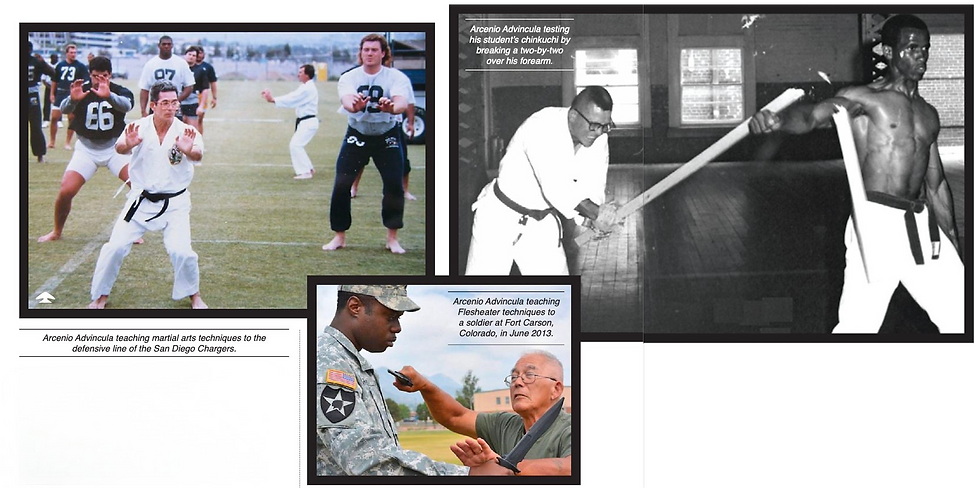

The American also capitalized on the component of Shimabuku’s system that revolved around cultivating power through body mechanics and control, what the old Okinawan masters called chinkuchi. Part of goju-ryu, chinkuchi gives the practitioner the ability to instantly transition from complete relaxation to full-body tension. That enables the student to effect the rigidity needed to penetrate targets, as well as to absorb impacts without sustaining damage.

Chinkuchi was the key to Shimabuku’s ability to drive nails into planks with the side of his hands and to Advincula’s ability to easily move people twice his size and 50 years younger with just an open-hand block.

Shimabuku began referring to Advincula as Katagwa, or “Kata Man.” Shimabuku selected the nickname because of the depth of his student’s understanding of kata, his knowledge of bunkai and his ability to make the bunkai work. On the surface, a kata is just a string of choreographed movements, but when analyzed under the guidance of a master like Shimabuku, its essential techniques, concepts, strategies and principles are revealed.

Many instructors teach kata, techniques and free fighting as separate entities. In contrast, Advincula learned — and subsequently started teaching — the notion that everything comes from kata. From the get-go, he was told what the key elements in the kata were and shown how they could be used in combat.

Graphic Artist

Advincula played a key role in designing the unique — and controversial — isshin-ryu patch. It incorporated the symbol for the art, the megami goddess, as the centerpiece. In February 1961, Shimabuku approved the design.

Unfortunately, the language barrier that stood between Advincula and the patch maker caused the design to be rendered incorrectly. Advincula had sketched it with a vertical fist that featured a thumb on top, just like the isshin-ryu punch, but the patch maker placed the thumb on the side — the way other styles of Okinawan karate teach. Also incorrect was the orange border: The crest was supposed to feature a gold border to symbolize purity and the idea that karate should never be misused.

Since the error and its subsequent propagation, Advincula has worked tirelessly to get the right version of the patch out to the public. He said he’s pleased that with every passing year, more martial artists are donning the crest that Shimabuku authorized.

Okinawan Ambassador

Throughout the years, Advincula has enjoyed an ongoing link to Okinawa. The Marines sent him there repeatedly, civilian life saw him living there on several occasions, his Okinawan wife served as the impetus for making familial visits, and cultural tours have had him guiding groups there for the past 20 years. The resultant training ops gave Advincula a chance to pursue the study of several other Okinawan arts, including shorin-ryu, goju-ryu and uechi-ryu.

One style the American picked up on the island and grew to admire was hindiandi kung fu. Originating in Southern China, it’s based on the concept of yin/yang. It uses two-man drills with rapid exchanges of punches, kicks and circular blocks. These moves, along with footwork designed to close the distance quickly and techniques designed to redirect an attacker’s momentum, made hindiandi an effective fighting system in the mind of Advincula.

Advincula was so taken with hindiandi that when the San Diego Chargers hired him to train their defensive linemen from 1987 to 1993, he turned to the art. “I got to experiment with them,” he said. “They are at close range and in your face, so you better have your stuff down. Ninety percent of what I taught and used with them was hindiandi.”

At age 49, Advincula had his work cut out for him with the Chargers, and it’s not surprising that initially he met with opposition from the players. His response? He devised a lesson that would start with him facing the linemen in a scrimmage, after which a snap was simulated before the full contact ensued. Witnessing the intensity of what had happened to the first lineman, the second player threatened to sue Advincula if the martial artist pulled his arm out of its socket. From that point on, Kata Man had their respect. As they say in the Marines, example is the language all men understand.

Military Man

Essential to understanding Arcenio Advincula is knowing that he served as a Marine for 24 years of his life. His discipline, work ethic and drive to make techniques work — no matter the conditions — stem from his time in the Corps. “When I graduated from boot camp,” he said, “I was convinced I was the best fighting machine in the world and knew you had to make it work no matter what you are doing, with whatever tools you have on hand.”

Those are a few of the lessons that carried Advincula through 1965, the year he first saw combat in Vietnam. Subsequent tours gave him more hands-on experience, which he put to good use when he became a drill instructor in the 1970s. Advincula went out of his way to teach the recruits skills that could save their lives in combat.

The karateka retired from the Marines in 1981, having obtained the rank of master sergeant, but he continued to teach the Marines how to fight with blades, as well as how to be successful in hand-to-hand combat. Recognition for his lifelong devotion to teaching Marines came in 2001, when he was acknowledged as a founding father of the revised Marine Corps Martial Arts Program. Advincula was awarded the title of Black Belt Emeritus.

Knife Visionary

In 1991 renowned knife maker Jim Hammond sought out Advincula in an attempt to create the ultimate combat knife. Designed to Advincula’s specifications, it acquired a name when someone sustained a cut after touching the blade and quipped, “That knife is a real flesh eater!” The description stuck, and the Flesheater quickly became one of Hammond’s bestselling tactical knives.

Three years later, James Byron Huggins had the Flesheater playing a pivotal role in his novel The Reckoning. Specifically, the blade is wielded by the book’s main character, a retired Delta Force member, and employed in multiple battles that used Advincula’s knife-fighting system as a frame of reference.

For those unfamiliar with the blade-fighting system: Advincula’s knife style is simple yet effective. It primarily uses the hammer grip and emphasizes attacking the opponent’s weapon hand before delivering a technique to end the encounter. Based on the escrima that Advincula began learning as a child, as well as his further studies in the 1960s, it also includes elements of isshin-ryu, making it an eclectic mixture of combat-proven techniques.

The Flesheater was picked up by Columbia River Knife & Tool, which began mass-producing it in 2012 under the more politically correct name “FE Model.” The company also offers a plastic version of the knife so enthusiasts can train realistically and safely. Since CRKT started marketing its line of blades — as the FE7, FE9 and FE9 Trainer — Advincula has been in demand to teach the tactics he created to make best use of this unique weapon.

Dedicated Teacher

For more than 40 years, Advincula has worked the seminar circuit in North America. In 2013 alone, at age 75, the karateka traveled tens of thousands of miles to spread isshin-ryu, kobudo, escrima and military CQC, as well as something that’s near and dear to his heart: Okinawan culture.

Back in 1960, an Okinawan newspaper reporter interviewed Tatsuo Shimabuku about the popularity of his style with U.S. Marines. Shimabuku didn’t say that he hoped his students would be the best fighters in the world or that he wished his art would gain popularity in the States. He said he longed for his homeland to be better understood through the practice of karate.

“If you want to understand Okinawan martial arts, then understand their culture,” Advincula said. “They have a lot to teach us. Okinawan karate is not about punching, striking and kicking for sport; it’s about learning to defend oneself if needed. It’s about courtesy and getting along with each other and sharing and living.”

In 2005 Advincula was recognized for his commitment to spreading Okinawan karate and kobudo when he received an invitation to a government-sponsored event designed to bring attention to the island as the birthplace of those arts. More than 250 senior karate instructors from Okinawa and Japan attended, along with just five foreigners.

Advincula, representing the United States and isshin-ryu, spoke about how Shimabuku had taught him almost 50 years earlier that karate was for peace and the transmission of culture.

Advincula remains committed to propagating the art of isshin-ryu, as well as the culture from which it sprouted. The 77-year-old still works out with his students, meticulously correcting their moves while wowing them with his speed, power and fluidity and trying to convey the message that karate is about much more than fighting.

“If only one [student] listens,” he said, “the effort was worth it.”