- Aug 20, 2024

- 6 min read

In ancient times, the Greeks developed a culture in which combat played a major role. Athletes prepared to fight unarmed in the “heavy events” — wrestling, boxing and pankration — at the many festivals held throughout the country, with most of the contestants dreaming of one day competing at the Olympiad. Consequently, the Greek people developed a thirst for violence, and the Olympic Games revolved around symbolic warfare.

All that explains why the Greek hoplite (foot soldier) was perhaps the most dominant and feared warrior of his time. This was especially true of Sparta, where boys were taken from their homes when they were as young as 7 so they could be groomed into fierce fighters.

The arms and armor these warriors learned to use were collectively referred to as panoply, meaning “all arms.” The average kit for an adult weighed between 40 and 60 pounds and included a shield, bladed weapons and defensive coverings. Those components are discussed in detail below.

The Shield

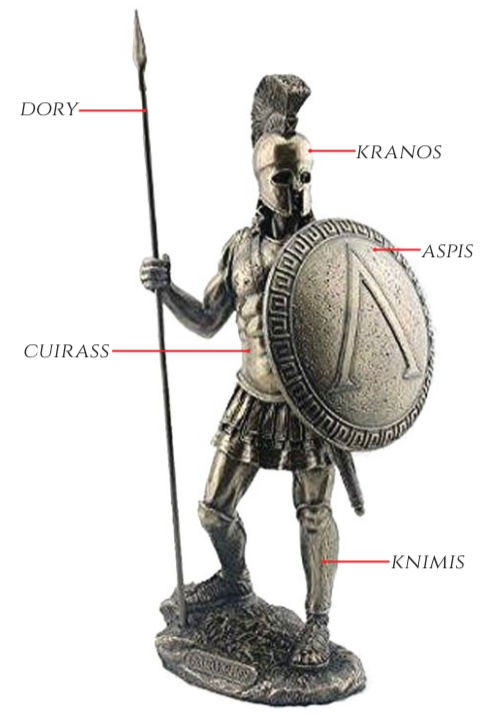

The shield (or aspis) was a deeply dished device constructed from wood. Some had a thin sheet of bronze on the outer surface, but often it was just around the rim. To keep it in place, the soldier held the antilabe (grip) on the shield’s edge.

This worked well enough, but later when the argive handle was created, the soldier could use his entire arm and shoulder to bear the weight of the shield rather than just his wrist. Now, Greek fighters were able to wield much larger and heavier shields, which they used not just for defense but also for offense.

Battlefield Note: It’s been theorized that the outward curvature of the shield served to give its owner additional breathing space when in close formation. The way the Greeks fought often entailed the use of phalanxes, which had warriors pressed together so tightly that breathing could be difficult. The concave side of the shield provided room for their chests to fully expand.

Unfortunately, the weight of the larger shield made it cumbersome to carry on long marches. And when a soldier had to retreat quickly in battle, he often would be forced to drop his shield — which might lead to his being ridiculed as a coward when he returned home.

The Spear

The dory was an iron-tipped spear used to administer killing blows with an overhand or underhand thrust. With its length of 6 to 9 feet, it served as the first line of attack. The dory typically had a leaf-shaped spearhead and a spike at the back. The spike was used if the spear- head broke or if a soldier needed to finish an enemy who’d fallen to the ground.

Battlefield Note: The spear’s iron head and heavy shaft made it effective for inflicting deep wounds to the throat and thighs of the enemy. Wielded right, it could even penetrate an opponent’s faceplate or body protection. Against the lighter-weight shields and armor of foreign foes (those not from other Greek city-states), the dory proved even deadlier, easily penetrating, for example, the wicker constructions used by the enemy during the Persian Wars.

While the butt-spike was useful for finishing wounded enemies who happened to be lying on the ground as a Greek formation advanced, it also had great utility in an active confrontation. When the leaf point was used underhand — that is, when the spear was wielded like a sword — a forward thrust at the opponent would most likely be blocked upward by his shield. To press the attack, a shield-edge thrust into the enemy’s shield would be effected, knocking the opponent backward and exposing his foot to a thrust from the butt-spike. That exposed foot, under the edge of the shield, resembled a lizard peeking from under a rock and may have prompted the Greek soldier’s slang for the butt-spike: lizard killer.

The chief advantage of the spear was that it enabled a soldier to keep his enemy at bay in battle. Being a single- handed weapon, it was held in the right hand, leaving the left arm free to support the shield. In the phalanx arrangement, the dory’s length proved effective for engaging multiple ranks of the enemy’s formation. This was especially true of the Macedonian Greeks, who liked to wield an 18-foot-long pike called a sarissa .

The Swords

At close quarters, the hoplite relied on a variety of edged weapons to cut, stab and slash his adversaries. The xiphos was a double-edged, one-handed sword that was employed when a spear couldn’t be used. The classic blade length was generally 20 to 24 inches, although the Spartans supposedly used blades as short as 12 inches during the Greco- Roman Wars.

The leaf-like shape of the xiphos lent itself to both cutting and thrusting. The origins of the design are not known; it’s believed to have existed since shortly after the first swords were fabricated. In Greece, early versions of the xiphos were cast in bronze, while during the Classical period, iron was used.

Battlefield Note: The kopis was a heavier sword with a forward-curving blade. Its shape made it especially effective in mounted warfare against infantry troops. Also a one-handed weapon, it averaged 3 feet in length, which made it roughly equal in size to the spatha, another Greek straight sword. The kopis is often compared to the shorter Nepalese kukri and the Iberian falcata. Because of its curvature, the kopis was often used to chop at an opponent’s weapon-bearing limb as soon as he moved into range.

A soldier in the higher ranks also carried a parazonian (Greek for “at the belt”). A short dagger that was regarded as a sign of prestige, it can be seen in Greek statuary.

The Armor

The hoplite’s defensive equipment included a bronze helmet (kranos), a pair of bronze shinguards (knimis) and a cuirass, a torso protector that was made of bronze or even layers of linen glued together.

The other parts of the warrior’s body were presumed to be protected by the aforementioned shield, so much so that additional armor was deemed unnecessary.

The Training

The ancient Greeks determined that the skills one learns from dance could serve a practical purpose in single combat, when nimble feet often meant the difference between dodging a spear and being impaled by it. Thus, war dances, collectively called pyrrhic, were emphasized in the soldier’s training. Similarly, various armed exercises were often accompanied by music from a lyre or flute.

Historical Notes: Plato once said, “The best dancer is the best warrior.” And in Homer’s Iliad, the Trojan prince Hector tells the hero Ajax that he’s not frightened by him because he knows the steps of the “deadly dance of Ares,” the god of war.

The changes in military tactics and in the education of youth instituted in the fourth century B.C. had a major effect on the development of armed combat as a sport in ancient Greece. Those who trained as athletes and made a name for themselves in the palaestra (school) were often best-equipped to distinguish themselves in war. However, many citizens looked unfavorably on this type of contest, claiming it was a pointless practice because the use of phalanxes left little room for a hoplite to act independently. For this reason, sports derived from armed combat were not part of most pub- lic festivals.

However, sporting duels between armed — and heavily armored — athletes became popular in the Hellenistic period, when several Greek city-states started awarding prizes to participants. Although the rules aren’t precisely known, scholars believe that the matches were meant to showcase expertise in hand-to-hand weaponry, flexibility and physical stamina.

The Iliad describes one such contest that was intended to inflict wounds. In the matchup, Ajax and Diomedes collided three times, with both failing to find their mark.

During the next attack, however, the weapon of Diomedes nearly pierced the throat of his opponent. Fearing fatal consequences, the spectators intervened, calling for an immediate stoppage.

The Tradition

It’s clear that the arms and armor of ancient Greece, along with the proven combat tactics and training methodologies described here, combined to forge battle-ready warriors who possessed fearsome skills and indomitable spirits.

For these fighters, there could be no retreat and no surrender. The qualities on which they relied are perhaps best summed up in a message a Spartan mother gave her son as he went off to war: “E tan e epi tan.”

Return with your shield victorious ... or carried home dead upon it.

Jim Arvanitis is a Black Belt Hall of Famer and pankration instructor. Known as the “father of modern pankra-ion,” he’s spent his life rebuilding and modernizing the ancient combat system of his ancestors. The author wishes to thank Chris Pangalos and John Thomkins for their assistance with this article. Pangalos is founder of The Warriors of Greece, a living-history re-enactment group, and Thomkins is his assistant. For more information, visit thewarriorsofgreece.com.