- Dr. Craig D. Reid

- Oct 29, 2023

- 7 min read

Updated: Nov 29, 2023

Wuxia films 1905-1982: Quasi Non-Fiction Wrapped in Fantastical Fight

by Dr. Craig D. Reid

The coolest wuxia film of the 1920’s, Burning of the Red Lotus Temple (1928)

Who could have guessed that the fate of the first 44 years (1905-1949) of wuxia cinema was heavily affected by the sexist attitudes of the Ching Dynasty? It all started in 1772, the year the Ching government banned females from performing on stage, which created the tradition of female impersonators in Beijing Opera.

However, realism demanded real women's bodies. So once film came around, women would be cast in female roles. During the silent era, being an actor was considered one of the lowest occupations around, so men would rarely risk losing face by becoming an actor. This opened the doors for actresses to be the cinematic heroes, and as weird as this may sound, this was highly detrimental to the industry, and it was not because of sexism.

When we left the first half of the Chinese Wuxia Xiaoshuo (wuxia novels) blog, the famous martial arts novels of Chinese yore created during the Warring State Period (481 BC–221 BC), had received the biggest commercial boost for their wuxia novels when in 1905, the first martial arts movie in history was filmed at Beijing’s Fengtai Photography Studio.

Tan Xin-pei in Dingjun Mountain (1905), the first film to feature martial arts.

Starring Chinese Beijing opera star Tan Xin-pei as General Huang Zhong, the silent film Dingjun Mountain dramatized the Battle of Mount Dingjun (A.D. 219) based on a chapter from the 14th-century wuxia novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Featuring opera-born fight choreography, it was the first film ever that featured martial arts action. For Tan, it was not a loss of face, yet using his opera face to elevate the honor of his traditional Chinese theatrical art.

By 1925, there were 175 movie companies in China’s major cities, 141 of them in Shanghai, that all focused on making love stories, Confucian morality tales and martial arts movies. It’s no stretch of the imagination that many wuxia films were made prior to 1925.

The first known full-length wuxia pian (wuxia film), thus oft considered the first Chinese martial arts movie, starred actress Fen Ju Hua in Swordswoman Li Feifei (January 1925) as a female wuxia hero that saves a woman from committing suicide who’s being forced into marriage.

It’s noteworthy that Feifei was produced by the eldest Shaw brother, Runje Shaw, when their Shanghai studio was called Tianyi Film Company. When the family moved to Hong Kong in 1957, they became known as Shaw Brothers, a tour de force in the wuxia film industry.

Probably the coolest 1920’s wuxia film was The Burning of the Red Lotus Temple (1928). Adapted from The Tale of the Extraordinary Swordsman, it was a 27-hour long extravaganza split into 19 feature length parts about a daring rescue of a general being held in a trap-infested temple that features insane, special effect-enhanced weapon fights. (see opening photo)

Rise, Exodus, Purge

By the 1930s, new directions evolved. Wuxia writers were not scholars tinkering with period fiction, instead they were money-making, newspaper serial writers with bold imaginations that dared to break socio-political rules as their heroes faced outrageous situations. Think of it as Chinese sword and sorcery events filled with demons, monsters, secret scrolls and magic spells.

These characters had extraordinary leaping abilities, could shoot flying swords and daggers out of their hands and weapons. When superheroes fought supervillains, they’d sit opposite each other and fight with their astral spirits, while Daoist and Buddhist priests remind us of humanity, as only they can attain cong jian zhong wu dao (from the sword, they have realized the way).

Starting with Chivalrous Swordsmen of the Sichuan Mountains, Huanzhu Louzhu (aka Li Shoumin) ended up running 27 novel franchises with an accumulative 100+ volumes that influenced the development of the wild and wacky Cantonese wuxia films of the 1950s and ‘60s, where heroes battling creatures, and beasts, and behemoths, oh my!, were par for the course. His novel Blades from the Willows (1946) was one of the first wuxia novels translated into English.

Another influential writer at that time who also churned out gobs of wuxia fiction was Wang Du-lu (aka Wang Baoxiang). He avoided dwelling on martial fantasies and heroic escapades, and instead focused on the social weight of the martial heroes, their love-lives, agonizing tragedies, and valiant sacrifices, and how all these pressures affected the heroes’ martial paths.

Hong Kong's Cantonese cinema arose when the Nationalist Government laid down the law that all films made in Shanghai (the Chinese Hollywood of the 1920s-1930s) had to be shot in mandarin, which forced a mass exodus of Cantonese speaking talent to Hong Kong.

Soon thereafter, the Nationalist Government heavily censored then banned these films because they were repulsive, and the government believed that many of their plots and themes would engage the populace toward rebellion, improper behavior, and political disorder.

In the late 1920’s, actress Jiang Qing dreamed of becoming an actress yet none of the 141 Shanghai film companies would hire her. This is the biggest mistake in Chinese cinema history.

Jiang Qing married Mao Ze-dong in 1938, and in the 1950s she became the head of the Film Section of the Communist Party's Propaganda Department. Only 20, pre-1949 films are known to have survived her destructive cleansing (fires) of the Chinese Proletarian Cultural Revolution.

Earliest known surviving wuxia film, starring Fan Xue-ping in Red Heroine (1929).

I had the privilege and pleasure to watch two big silent films of that era that survived the cleansing at a nationwide traveling film festival called Heroic Grace in March of 2003 at UCLA: the Red Heroine (1929) starring actress Fan Xue-ping; and Swordswoman of Huangjing (1930), which starred Sammo Hung’s grandmother Xu Chin-fang. The production values matched the American films, yet the choreographed fights were way ahead of their American counterparts.

No one knows how many wuxia films were erased from history and especially the timeline of their existence and growth since 1905 to 1949. Furthermore, wuxia novels were now also banned in China and Taiwan. This left only Hong Kong to be the torchbearer for wuxia novels and films.

Hong Kong, Land of the Rising Wuxia Pian

In the early 1950s, Hong Kong based wuxia novelists Liang Yu-sheng and Jin Yong (aka Louis Cha), were influenced by Western literature and the freedom of thought attitude that existed during British Colonial times, as they infused their characters with narcissistic lifestyles that embraced the idea of non-conformity and won over the masses by placing their heroes during historic Chinese times when China was under foreign rule, i.e, now Britain in Hong Kong. Their success circled around honoring the sensibilities and schticks created by Huanzhu and Wang.

Some of Jin’s well-known novels that have multiple must-see movie adaptations are Legend of the Brave Archer (1957), The Flying Fox of Snowy Mountain (1959), Demi Gods and Semi Devils (1963) and The Smiling, Proud Warrior (1967). For Liang, Story of the White-Haired Demon Girl (1959) and Three Women Warriors (1960) also has cool film and TV adaptations.

When Mandarin filmmakers arrived in Hong Kong in the 1950s, they held wuxia film in contempt as reflected in their preference for Chinese opera and wen yi (literary art) films. Yet by the mid-1960s Shaw Brothers Studios and the rise of directors like King Hu and Chang Cheh,

Mandarin filmmakers began to overcome the prejudice of the wuxia film in Mandarin cinema.

With their new-wave style of kinky plots, unique fight-detailed choreography with sumptuous sight gags, camera choreography and pacey editing, Chang and Hu revolutionized the wuxia film by instilling a new literary dynamic via the rise of two outstanding wuxia novelists: Taiwan based Gu Long; and Shanghai born turned prolific screenwriter Ni Kuang.

Ni churned out over 300 scripts, many of them for Chang and another influential wuxia film director Chu Yuen, who also filmed many of Gu’s novels that were scripted by Ni. Gu’s brusque language lined his cloak and dagger sensibilities, while using hidden danger tropes akin to the secretive natures of James Bond and western detective thriller genres. His neo-twisted plot designs attracted the younger generation of Chinese filmgoers with films like Jackie Chan’s To Kill With Intrigue (1977) and Magnificent Bodyguard (1978).

Jimmy Wong Yu, on the left, in One-Armed Swordsman (1967)

Between 1965-1985, Shaw Brothers kickstarted a new era of wuxia films by producing 150 wuxia movies. Two heavily influential films that defined this age’s beginning were the Chang directed, Ni Kuang written and Jimmy Wong Yu starring, manly-man epic One-Armed Swordsman (1967). Inspired by the one-armed character in Jin’s novel The Eagle Lovers (1959) the movie featured the fight instructor duo chops of Liu Chia-liang and Tang Chia.

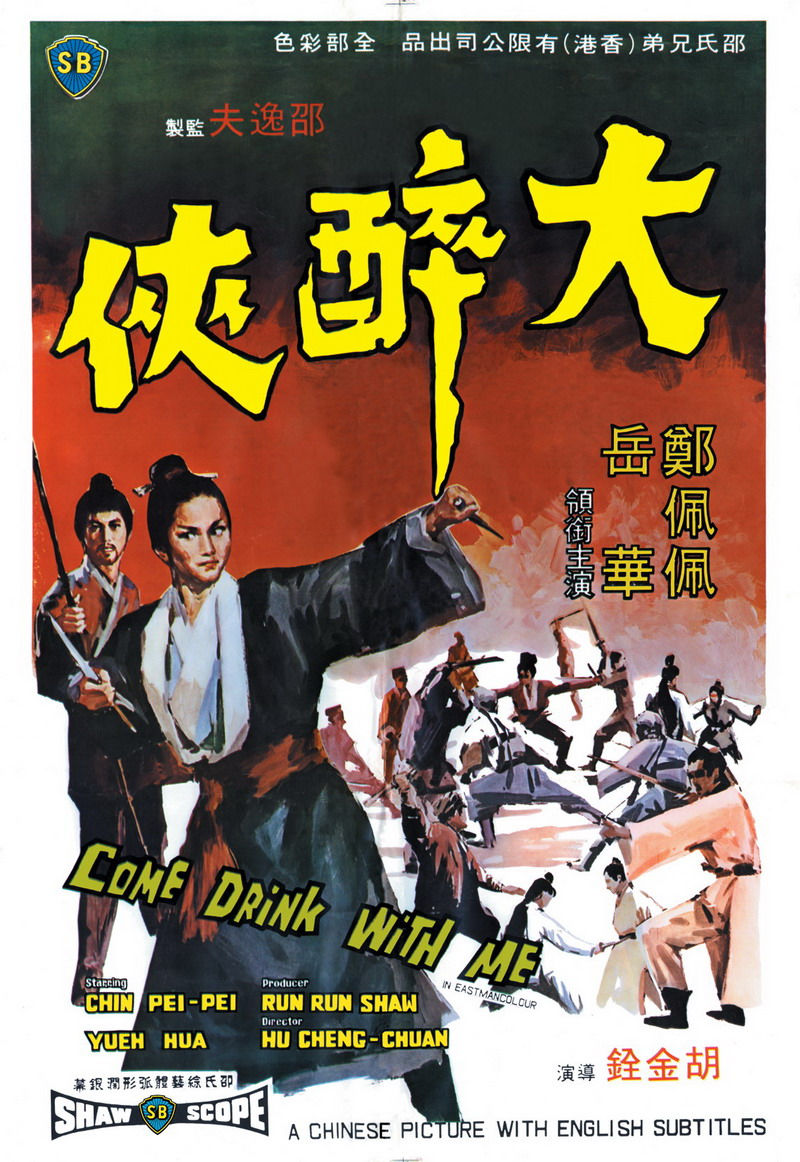

The second was the King Hu directed, co-written by Ding Shan-xi (Ding directed the first kung fu movie I starred in) and headlined the first official Queen of Kung Fu films Cheng Pei-pei as a swordswoman in Come Drink With Me (1966). The film highlighted the fight instructor skills of Hang Ying-jie (lead villain in Bruce Lee’s Big Boss (1972)) and his assistant Sammo Hung.

As the kung fu and the wuxia films of the times started to lose their luster, due to Hong Kong's industry-destroying copy-cat mentality, Jackie Chan created a new genre of martial art films called wu da pian (fight films with martial arts) that put wuxia movies on the chopping blocks.

With films like Project A (1984) and more officially via Police Story (1985), Chan intelligently combined athleticism, martial arts and dangerously outrageous stunts wrapped in more contemporary themes and settings. He was now even a bigger man on campus.

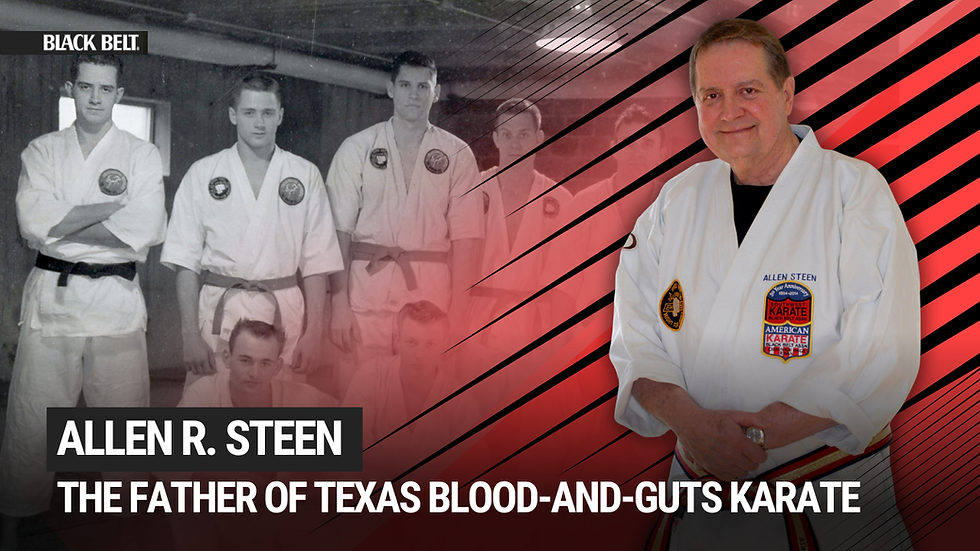

Yet in the final chapter of this wuxia story, a real hero of wuxia who graduated from the University of Texas, Austin, stepped up and saved the day. How? The Rise of Fant-Asia.

*Note: Before 1983, When Chan’s Golden Harvest kung fu films Snake in the Eagle Shadow (1978) and Drunken Master (1978), overpowered the Hong Kong film industries, Shaw Brothers had director Chang and fight director Liu Chia-liang create a new martial art genre, guo shu pian (national art films). The 36th Chamber of Shaolin (1978) is a famous early example.

Poster Art for Come Drink with Me (1966)

Image Sources:

Photo 1: The coolest wuxia film of the 1920’s, Burning of the Red Lotus Temple (1928)

Photo 2: Tan Xin-pei in Dingjun Mountain (1905), the first film ever to feature martial arts.

Photo 3: Earliest known surviving wuxia film, starring Fan Xue-ping in Red Heroine (1929).

Photo 4: Jimmy Wong Yu in One-Armed Swordsman (1967)

Photo 5: Poster Art for Come Drink with Me (1966)