- Dec 2, 2024

- 6 min read

Updated: Dec 13, 2024

Every traditional martial art exists in the present because at one time in the past, it was used successfully in battle. It would have been illogical for warriors to pass down strategies and techniques that failed to function in fights. End of story.

In part because of geography, most cultures and classes were pitted against the same enemies, often for long periods of time. Therefore, it can be assumed that most fighting systems developed to neutralize a specific enemy.

Case in point: In Japan, jujitsu was created to combat the samurai, with their iconic weaponry and their unique way of fighting. Now, the fact that most members of a given adversarial group probably fought in similar ways, one can argue that this could limit the efficacy of the art that’s being used against said group if it was pitted against a different group.

It follows, then, that any art that was battle-tested against two enemy cultures would be more effective than a style that faced only one. And it follows that if an art was forged in three crucibles that resulted from prolonged clashes with three mighty nations, it would have the upper hand.

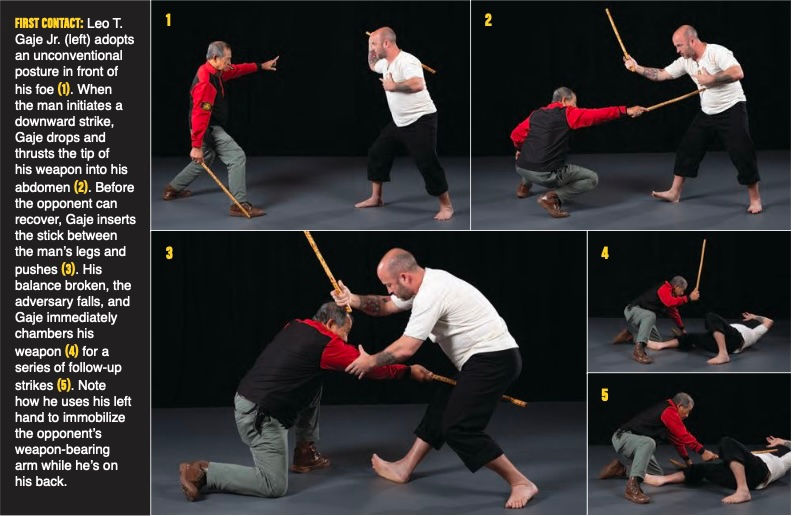

Such a system does exist, and it’s called pekiti tirsia. This form of kali is helmed by Leo T. Gaje Jr., and it’s being used by millions of military men and women around the world for the very reasons mentioned above.

Crucible No. 1

Gaje was born in 1938 on the island of Negros in the Philippines. When he was just 6, he began training under his grandfather, Conrado Tortal. The reason the patriarch put his only grandson on the martial path so early was eminently practical.

“He said, ‘I will train you so you can protect your property and family,’” Gaje said. “Every family in the Philippines had to be able to take care of themselves.”

Historically, a significant part of that mission of protection was to fight against the Spanish, he added.

You see, in the aftermath of Ferdinand Magellan’s arrival in 1521, Spain took gradual control of the Philippines. And the Spanish, with their blades, ruled with an iron fist.

“Often, one member of a family would go out to observe how the Spaniards used their swords — they were intelligence agents, in a way,” Gaje said. “In my family, my grandfather had three brothers, and they observed the fighting system of the Spaniards. They would report to my grandfather, then do clinics on the type of fighting they saw. Most of it was using the blade from long range.”

With the intel, Gaje’s grandfather focused on footwork — specifically, how the family might use close-range methods to defeat their enemies.

“My grandfather and his brothers analyzed the footwork of the Spaniards step by step,” Gaje said. “They saw that most of the movement was linear, so they developed a way to open it up, which is the open triangle. From that base, they were able to strategize their methodology. They used diagonal lines because a diagonal line is a protective line when you slash and thrust. They were looking for a way to attack up close that was not counterable, meaning to say there was no way to block the technique.”

The brothers determined that there are two ways to fight when blades are involved: with weapon contact and without weapon contact.

“If one blade makes contact with another blade while blocking, it takes time to recover,” Gaje said. “So they studied angulation [to avoid that]. If your angle is coming in this way, I go that way. If you go high, I go low. All this was part of a building process — they did it every day.

“Whenever they developed a new technique, they would go on a test mission. The brothers would go out and fight with the Spaniards. One hundred percent of the techniques we teach now worked then. That’s why we teach them — and it’s why in pekiti tirsia, we always say that every technique cost lots of lives.”

Gaje’s grandfather often talked about the cultural discipline he and his brothers were adding to what the Spanish practiced, Gaje said.

“He called it the actual expression of combat. It was about the counter of motion before attack time, which is where [the acronym] COMBAT comes from.

“The system they created — pekiti tirsia — had only 12 methods, one for each month of the year. In one month, you had to learn one method. The first three months were for skill development. The next three months were for specialization. The next three were for mastery. And the final three were for testing and building confidence. It all had to be done quickly because they were fighting the Spaniards.”

To polish their skills for actual use, the brothers would begin with hardwood sticks, Gaje said. “They would hit water for power development and to feel resistance. They also worked on speed so their actions couldn’t be trapped or easily countered. And, of course, they focused on using footwork to get in close — pekiti tirsia means ‘close-quarters techniques.’ It isn’t designed for long range.”

The goal, Gaje reiterated, is to take action before the opponent’s strike comes to fruition because then you don’t need to spend time blocking.

“If you give me a slash, I will slash, also,” he said. “Counter of motion before attack time means that as soon as there is one motion from your opponent, you’re there. It can be any first move.”

Such combat efficiency came as a result of three centuries of Spanish control of the Philippines, Gaje added. “It enabled us to develop a blade technology that was superior to that of the Spaniards.”

Crucible No. 2

“Eventually, eight provinces of the Philippines revolted against Spain,” Leo T. Gaje Jr. recounted. “After the revolution ended, Spain negotiated in the Treaty of Paris of 1898 to sell the Filipinos to the Americans at $3 per head. Imagine that! The Philippines was considered the property of Spain, but why did they have to sell the Filipino people to America? Why not the land?”

Initially, the Filipinos celebrated their liberation from Spain, but the reality of American rule quickly soured the victory. “We started fighting the Americans with guerrilla tactics. Our success caused Gen. [John] ‘Black Jack’ Pershing, who served in the Philippines, to tell the War Department, ‘We cannot win the war like this. These Filipinos are so savage.’”

In response, Pershing recommended that the U.S. military develop a handgun capable of stopping the Filipinos. “That’s why they created the .45-caliber,” Gaje explained. “At close range, when Filipino fighters came at Marines with their bolo [knives] raised, a .45 was needed to stop them. The .38 didn’t work.”

The Philippine-American War persisted until 1935, when the U.S. established a Philippine commonwealth. “That was the only way for the Americans to say they did not lose in the Philippines,” Gaje said. “They said, ‘We’ll give you a commonwealth.’ We said, ‘What are the conditions?’ Among other things, they said, ‘Your men will be in the U.S. Armed Forces under Gen. MacArthur.’”

Despite the uneasy truce, relations between the Filipinos and Americans improved until 1941, when Japan invaded the Philippines. With a force of 200,000 troops, supported by battleships, tanks, and planes, the Japanese quickly overtook the archipelago.

Crucible No. 3

The war with Japan was a grueling ordeal. During the occupation, Filipinos and the remaining Americans waged relentless resistance. “The Filipinos and the Americans who were left fought back,” Gaje said. “But there was no sign that we were winning because we were outnumbered — and there was no support from the U.S. because it was responding to the Pearl Harbor attack. The Americans in the Philippines were totally dependent on the Filipinos for support. Many Filipinos sacrificed their lives in defense of the Americans.”

This period saw countless clashes with the Japanese, who wielded firearms and swords, while the Filipinos often relied on their traditional blades. Looking back, Gaje views this time as an unparalleled crucible for refining Filipino combat techniques.

Modern Beneficiaries

Today, pekiti tirsia, honed through these three historic conflicts, is a cornerstone of military training in the Philippines.

“It’s mandated,” Gaje said. “They start with the stick, which is a training tool. As they progress, they learn the knife. Of course, the stick can be used as a weapon. If you have a hardwood stick, which is very strong and heavy, you can be flexible — you can stop a person without killing him.”

The reach of pekiti tirsia extends far beyond the Philippines. “More than 1.2 million people in the Indian military do pekiti tirsia,” Gaje said. “And there’s another 700,000 in Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka. The U.S. Marines learn it, too, as do the militaries of Japan, Singapore, Malaysia, Korea, even China.”

Why do so many militaries adopt this art? Gaje provided an answer rooted in practical warfare: “When you’re fighting a war, there’s no kicking or punching. But why do they need the blade? During training in the Philippines, a test mission was sent to fight the Muslim extremists. The Philippine force recon marines, who are trained in pekiti tirsia, learned that in battle, the blade demoralizes the extremists.

“Our military is now feared by the extremists because we have a force inequality: If they use a blade to cut the neck of one of our people, we will use the blade to chop them to pieces. The only martial art in the world that is tested every hour of the day is pekiti tirsia, and the military knows this.”

Photography by Brandon Snider