- Floyd Burk

- Aug 19, 2024

- 8 min read

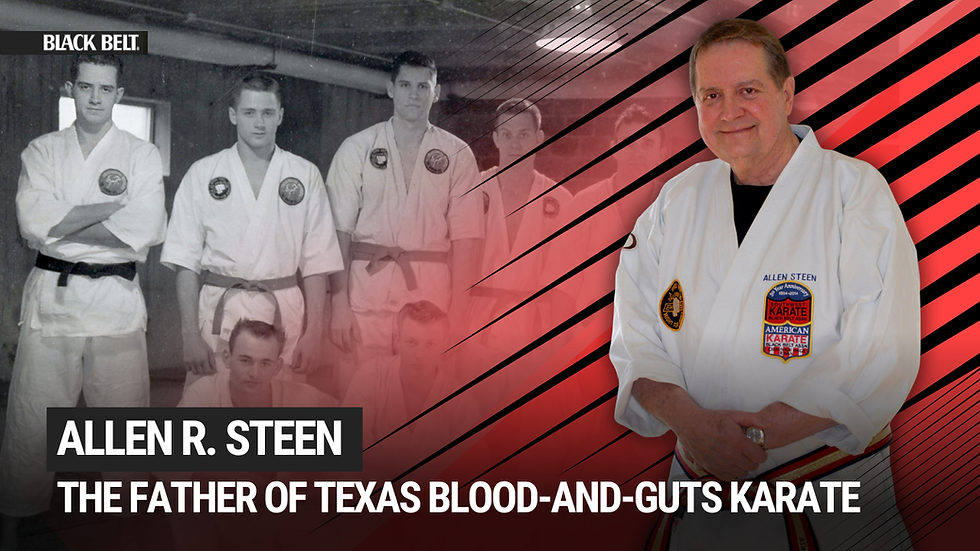

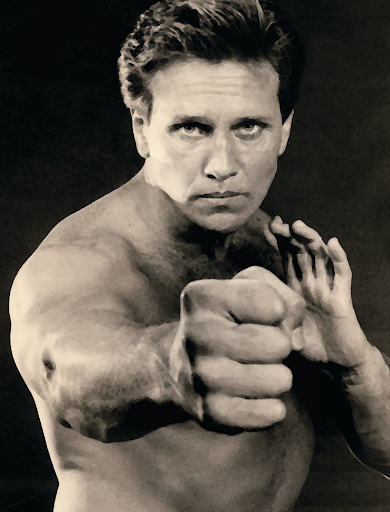

From the time he entered his first competition —where he won both the black-belt sparring and the black- belt kata divisions — until he emerged as full-contact kickboxing heavyweight world champion, Joe Lewis was the most colorful personality in the martial arts.

A two-time Black Belt Hall of Famer, Lewis brought quickness and finesse into the ring, along with the power to unleash a knockout punch or kick from either side. During his competitive years, he was perhaps the most intimidating adversary any martial artist could have.

Then there was the other side of Lewis, one that was equally intriguing. He was a teacher, an innovator, a role model and a mentor. Those two very different facets are what made Joe Lewis such an influential force in American karate. Here is the Warrior Way of Joe Lewis.

Motivation to Teach

Lewis observed that “only about 10 percent of the people in martial arts enjoy combat or any type of sparring.” That’s likely what motivated him to begin conveying his tactics and strategies to all who wanted to learn. He devised different ways to connect with those who claimed they couldn’t fight. He advised them to stay away from fancy moves and stick with practical applications related to their objectives. “You don’t have to be flashy,” Lewis would say. “You have to be fundamental.”

Because he was a fighter at heart, Lewis sought to teach others to unleash their inner warrior. He preached that warriors are never bound by useless or outdated moves; they have to be able to count on every technique they throw. And that’s exactly how he fought: He stuck with the basics, moves he’d polished through years of hard work. As such, he could step into the ring with complete trust in every technique he planned to use, and that’s the type of confidence he sought to instill in others.

Stances

Lewis disliked the word “stance.” He preferred to use the term “being grounded.” To him, that didn’t mean being stuck or rooted. It meant being in a combat posture that gave him the stability he needed to unload a power punch or kick.

His combat posture wasn’t a boxing stance, a karate stance, a kickboxing stance or a grappling stance. Rather, it was a position from which he could execute a lead-hand punch or lead-leg kick, as well as techniques using his rear-side limbs. The nuances of the perfect fighting posture, he said, depend on the person implementing it.

“It is a position that is uniquely yours,” Lewis explained. “Here, you develop that emotional demeanor, that kind of ambiance where you feel like [you’re] grounded and can unload an effective punch or kick. Defending [yourself] from here is no problem.”

Footwork and Movement

Two aspects of training that are often overlooked by modern warriors are footwork and movement. Lewis taught that they’re vital for shaping a strong defense and enabling you to “connect” with an opponent when you unleash a punch or kick. To maximize your effective- ness, he said, you should view footwork and movement as steppingstones to rhythm, broken rhythm, timing and interrupted motion.

Lewis was especially fond of using lateral footwork. He’d teach students to start in a fundamental combat position, firing off kicks and punches while stationary. Next, he’d direct them to execute the same moves with a rhythmic motion that might include advancing and retreating, moving from side to side or stepping forward at different angles. Of course, all movement needs to be fluid, he said.

Then Lewis would delve into target relocation: moving your head and/or body off the line of fire. Again, the emphasis was on staying relaxed and striving to be untouchable. He would have them add feints, fakes and strategic setups while in this “fluid state of consciousness.”

Hand Positions and Blocks

“Most schools spend 80 to 90 percent of their time teaching students to kick and punch and only about 10 percent of their time working on their defensive skills,” Lewis said. “I do not agree with this imbalance.”

Part of the remedy, he said, is to keep your hands high to protect your head and position your elbows in front of your rib cage. Lewis was just as adamant about his next point: When you punch or kick, try to have one hand touching your head so you can readily use it to intercept a head butt, an elbow or anything else that approaches. Either hand can serve that purpose, he said. If you happen to be a fighter who uses your lead hand to execute jabs, hooks, fakes and other probing maneuvers, he stipulated, you may have to use your shoulder to protect your chin.

Instead of conventional karate blocks, Lewis advocated the “pendulum block.” He’d teach the concept this way: Start with your lead hand at 12 o’clock and your elbow at the center of the imaginary clock’s face. Rotate that arm downward to 6 o’clock, placing your arm against your side. Your arm is now like a pendulum that can swing to block an incoming kick or punch, protecting your kidneys and floating ribs in the process.

You can execute the pendulum block while moving backward, Lewis said. Its effectiveness will be enhanced by rolling your elbow, and your groin can be protected by your hip.

Hand Techniques

“Boxing-type punches like the jab, hook, cross, uppercut and overhand are the most natural, practical and fluid,” Lewis explained. He said his favorite was the lead-hand hook, which he often elected to launch into his foe’s body because most people forget to practice defense against low-line punches.

On occasion, Lewis would teach students to double up on the hook. He’d have them throw a jab and follow up with a pair of fast hooks to the head or body. For versatility, he might tell them to add an elbow strike, spinning backfist or spinning bottom fist.

Leg Techniques

Lewis often said that his two favorite kicks were the lead- leg side kick and the cross-kick. He practiced the side kick regularly on the heavy bag, sometimes doubling up by kicking the bag, making it swing and nailing it again on the return. Not surprisingly, he advised students to engage in similar sessions.

The cross-kick Lewis did was a power roundhouse thrown with the rear leg. The way he taught it didn’t entail kicking and then stopping to retract the leg. You just throw the kick, hit the target and continue the movement for a 360-degree pivot, which puts you back in your original position. One of his rules for doing the cross-kick: Ensure that the arm you’re using to protect your kicking side is ready to do a pendulum block in case of a counter.

Lewis also favored a number of karate kicks, including the spinning back kick and ax kick. He liked to do double- and triple-kick combinations to keep his opponent off-balance, dissuade him from closing the gap and set him up for one of his faves: a rear-leg power kick. “The speed kicker may give you some problems, but the power kicker is the one who will scare you the most,” he said. “That’s why I believe in power kicking primarily.”

Defensive Tactics

“To reach your potential in the fight game, you must use your mind as the supreme weapon that it is,” Lewis said.

“You must understand how to keep your opponent from getting into his set position. This is what we call ‘set-point control.’”

He explained that doing this involves cultivating the ability to change the speed or direction of a technique to break your adversary’s rhythm. “This is what we call ‘broken rhythm,’” he said. “It makes no sense to square off with your opponent and walk in and just start banging away while putting yourself at a disadvantage when you can use your opponent’s body language to tell what he’s going to do and when he’s going to do it.”

Lewis taught that there are two ways to break your opponent’s rhythm: One is physical and one is psychological. But before you can disrupt someone else’s rhythm in a fight, he said, you need to understand how people implement rhythm and how it can be controlled.

“You have to learn how to read people,” he said. “The way they walk, sit, talk, breathe or move their hands will tell you lots of things. You can watch which part of a person’s body controls the rest of their body. Some people’s mind kind of wanders as their body passively follows. Others send off signals of a strong mental intensity, where they are looking way ahead while carefully guiding their body.”

You can begin to get a reading on your opponents’ rhythm just by watching them don their safety equipment before a match, he explained. “If their movements are sudden and jerky, they have a fast rhythm. If they move slow and casually, they have a slower rhythm. The person whose lips are pressed together and forehead is tensed up has a fast rhythm, whereas the person whose muscles around the cheekbones are relaxed has a much slower rhythm.”

Anyone who was fortunate to see Joe Lewis in action would notice that he always studied his opponent’s movements and mannerisms: how the person exited a car and walked into the arena, how he did his stretches and warm-ups, how he entered the ring. If Lewis saw an adversary casually drop his right shoulder and arm while walking, he’d stay alert for the habit to manifest in the ring. If it did, he’d have his left hook ready.

Setups

“As you square off against your opponent, you can set him up by doing this,” Lewis said when explain- ing broken rhythm. “When you trigger your initial move, make your techniques very explosive, fast and hard. Try that a couple of times [to] get him used to that type of trigger squeeze. Then, all of a sudden, the next time you squeeze the trigger, your move- ment is more relaxed [and] casual, allowing you to catch [him] totally off-guard.

“You also can do the reverse of this. Try a couple of yin-type approaches with soft, low-keyed, casual probes toward your opponent, moving your hands. You softly calm him down as you go toward his perimeter and pull out. You do this a couple of times, playing a little cat-and-mouse game, then in the middle of your movement, you change the essence by going from yin to yang.”

Such was the way Lewis taught the “speed change- up,” one of his favorite examples of broken rhythm. Lewis advocated using another entrapment that involves changing your speed and direction. “You probe in and out a couple of times and get your opponent used to seeing you coming up near the firing line and pulling out,” he said. “You begin to taunt, tease or lure your opponent into the entrap- ment, where they try to snap back and throw some counters at you. Then you probe in once more, but this time, you stop short of the firing line — his defensive perimeter. You leave your feet right where they are and rock your upper body backward like you’re going back to your starting position.

All of a sudden, you rock forward and explode with a punch or kick. So you have a sudden change in direction, a sudden change in speed and a sudden change in essence.”

Also of value are tactics that use inner rhythm, he said. “You can square off with your opponent and set a very fast inner tempo where you appear fast, aggressive, even a bit ferocious. All of a sudden, you generate a more passive type of inner rhythm, where you look very apologetic and yielding — like your opponent can run right over you. You’re just playing possum, drawing [him] into the entrapment. Then you switch gears again and hit him.”

Clearly, Joe Lewis wasn’t just a physical fighter; he was also an intelligent fighter. Fortunately for all of us, this wise warrior was more than willing to share his training and fighting secrets in an effort to enable others to follow in his footsteps.

Floyd Burk is a San Diego–based 10th-degree black belt with half a century of experience in the arts. To contact him, visit the Independent Karate Schools of America website at iksa.com.